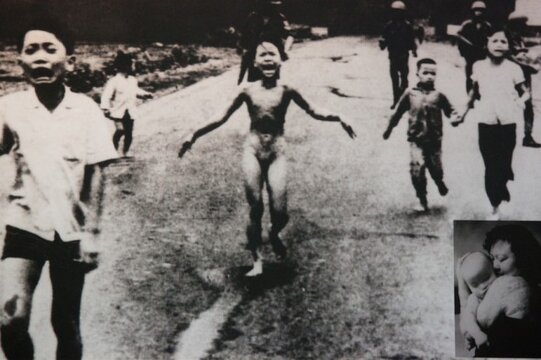

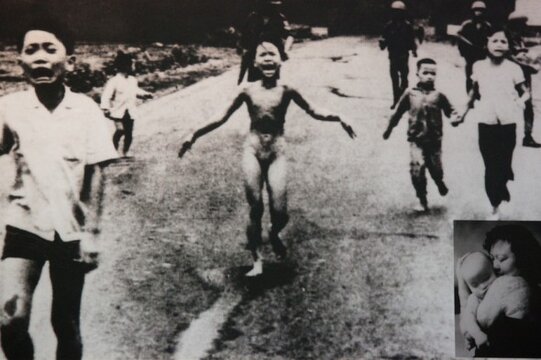

[Excellent article that asks the burning question, when is enough enough, and when is not enough, detrimental to public awareness? —chris]

Article HERE:

[From The Atlantic by Torie DeGhett 8.8.14]

The Iraqi soldier died attempting to pull himself up over the dashboard of his truck. The flames engulfed his vehicle and incinerated his body, turning him to dusty ash and blackened bone. In a photograph taken soon afterward, the soldier’s hand reaches out of the shattered windshield, which frames his face and chest. The colors and textures of his hand and shoulders look like those of the scorched and rusted metal around him. Fire has destroyed most of his features, leaving behind a skeletal face, fixed in a final rictus. He stares without eyes.

On February 28, 1991, Kenneth Jarecke stood in front of the charred man, parked amid the carbonized bodies of his fellow soldiers, and photographed him…The image and its anonymous subject might have come to symbolize the Gulf War. Instead, it went unpublished in the United States, not because of military obstruction but because of editorial choices…

The U.S. military has now abandoned the pool system [for reporters in a war zone] it used in 1990 and 1991, and the Internet has changed the way photos reach the public… Some have argued that showing bloodshed and trauma repeatedly and sensationally can dull emotional understanding. But never showing these images in the first place guarantees that such an understanding will never develop. “Try to imagine, if only for a moment, what your intellectual, political, and ethical world would be like if you had never seen a photograph,” author Susie Linfield asks in The Cruel Radiance, her book on photography and political violence. Photos like Jarecke’s not only show that bombs drop on real people; they also make the public feel accountable. As David Carr wrote in The New York Times in 2003, war photography has “an ability not just to offend the viewer, but to implicate him or her as well.”

As an angry 28-year-old Jarecke wrote in American Photo in 1991: “If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.”

Article HERE:

[From The Atlantic by Torie DeGhett 8.8.14]

The Iraqi soldier died attempting to pull himself up over the dashboard of his truck. The flames engulfed his vehicle and incinerated his body, turning him to dusty ash and blackened bone. In a photograph taken soon afterward, the soldier’s hand reaches out of the shattered windshield, which frames his face and chest. The colors and textures of his hand and shoulders look like those of the scorched and rusted metal around him. Fire has destroyed most of his features, leaving behind a skeletal face, fixed in a final rictus. He stares without eyes.

On February 28, 1991, Kenneth Jarecke stood in front of the charred man, parked amid the carbonized bodies of his fellow soldiers, and photographed him…The image and its anonymous subject might have come to symbolize the Gulf War. Instead, it went unpublished in the United States, not because of military obstruction but because of editorial choices…

The U.S. military has now abandoned the pool system [for reporters in a war zone] it used in 1990 and 1991, and the Internet has changed the way photos reach the public… Some have argued that showing bloodshed and trauma repeatedly and sensationally can dull emotional understanding. But never showing these images in the first place guarantees that such an understanding will never develop. “Try to imagine, if only for a moment, what your intellectual, political, and ethical world would be like if you had never seen a photograph,” author Susie Linfield asks in The Cruel Radiance, her book on photography and political violence. Photos like Jarecke’s not only show that bombs drop on real people; they also make the public feel accountable. As David Carr wrote in The New York Times in 2003, war photography has “an ability not just to offend the viewer, but to implicate him or her as well.”

As an angry 28-year-old Jarecke wrote in American Photo in 1991: “If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.”

![Capa%2C_Death_of_a_Loyalist_Soldier[1].jpg Capa%2C_Death_of_a_Loyalist_Soldier[1].jpg](https://www.theparacast.com/forum/data/attachments/4/4064-5167c4ea0181e3f0d2dc3dc9c6f58bb4.jpg?hash=UWfE6gGB4_)