The point I'm making is that we've gotten to the point where the MBP ( duality ) is no more resolvable than the problem of existence itself, which is also an age old problem that will probably never be fully understood. Therefore the solution to the MBP is that there is no solution. We can only accept that there are minds and bodies and deal with that situation as a given. By accepting what is, the two become one & neither, and in doing so, the "problem" vanishes, and we can make practical advancements.

But above you say:

"This to me seems to be the case with minds and bodies. Both exist, and we may never know all the answers as to how exactly everything about them comes into being, just like we don't know everything about how a magnetic field comes into being. All we know are the situations that make it happen. Isn't learning that good enough?"

Maybe not contradictory, but I think these are not the same positions:

1. The solution to the MBP is that there is no solution.

2. We may never know all the answers ... (because I think is trivially true of everything we know anything about) and therefore can't lead one to conclude (1) ... do you think we will or could know something more about how a magnetic field comes into being? Not just a detail, but something as basic as what we already know? Is there no more possible revolution on the order of Copernicus?

3. not one of your positions (I don't think) we know all we

can know about the mind body problem

For example if mind and body were correlated to some third thing, or mind and body stand in relation such that body is necessary but not sufficient, that would be worth knowing.

Formulating the problem as Nagel did (somewhere) that one could look at a brain scan of someone eating chocolate and know what it it like to eat chocolate seems impossible, (although "objective" and "subjective" are words given opposite meanings and may not be the actual facts of experience) formulating it as McGinn does:

"Now I want to marshall some reasons for thinking that consciousness is actually a rather simple natural fact; objectively, consciousness

is nothing very special. ... But now, think of these various aspects of mind from the point of view of evolutionary biology. Surely language and the propositional attitudes are more complex and advanced evolutionary achievements than the mere possession of consciousness by a physical organism. Thus it seems that we are better at understanding some of the more complex aspects of mind than the simpler ones. Consciousness arises early in evolutionary history and is found right across the animal kingdom. In some respects it seems that the biological engineering required for consciousness is less fancy than that needed for certain kinds of complex motor behaviour. Yet we can come to understand the latter while drawing a total blank with respect to the former. Conscious states seem biologically quite primitive, comparatively speaking. So the theory T that explains the occurrence of consciousness in a physical world is very probably less objectively complex (by some standard) than a range

of other theories that do not defy our intellects. If only we could know the psychophysical mechanism it might surprise us with its simplicity, its utter

naturalness."

does not sound impossible (though he argues we will not understand it for other reasons) and makes nothing of the "problem" of "self-reference' in understanding it as he argues it is just a relatively simple natural mechanism.

So if we had the same level of knowledge of "the building blocks" of consciousness - as we do of NAND and NOR gates, would we not understand how to make consciousness and resolve the mind body problem as surely as we have the 4 billion transistor smart phone problem? Or perhaps we would understand that it can't be engineered as its not a machine. Either way, we would have what we would think of as a full understanding which is

not "know all the answers as to how exactly everything about ... etc etc". Or is there some principle you can point to that says we cannot have this level of understanding, because that too, would be worth knowing.

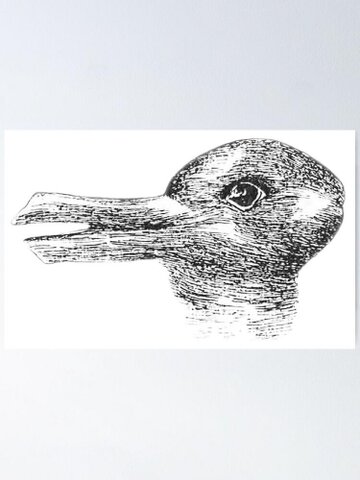

The question I think needs answering is how the conscious mind behind or beneath the eyes brings about the sudden recognition of the alternative interpretation of what is seen in the dual image. How much more do we have to learn about the nature of consciousness before we can answer that question?

The question I think needs answering is how the conscious mind behind or beneath the eyes brings about the sudden recognition of the alternative interpretation of what is seen in the dual image. How much more do we have to learn about the nature of consciousness before we can answer that question?