-

NEW! LOWEST RATES EVER -- SUPPORT THE SHOW AND ENJOY THE VERY BEST PREMIUM PARACAST EXPERIENCE! Welcome to The Paracast+, eight years young! For a low subscription fee, you can download the ad-free version of The Paracast and the exclusive, member-only, After The Paracast bonus podcast, featuring color commentary, exclusive interviews, the continuation of interviews that began on the main episode of The Paracast. We also offer lifetime memberships! Flash! Take advantage of our lowest rates ever! Act now! It's easier than ever to susbcribe! You can sign up right here!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Consciousness and the Paranormal — Part 4

- Thread starter Gene Steinberg

- Start date

Free episodes:

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Pharoah

Paranormal Adept

By way if contrast to Evans cf Dummett's book 'The seas of language' Chapter "what is a theory of meaning (I)" first couple of pages.

@Constance re the B&T review... interesting I thought, the reference to theology and Christianity

@Constance re the B&T review... interesting I thought, the reference to theology and Christianity

Zebra or the Logos

Skilled Investigator

In your opinion, is the work of Julian Jaynes at all relevant to consciousness studies? Is The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind something that one would, today, encounter in graduate studies of this field? Do you think it could provide a useful interpretive schema for the study of the paranormal and UFOs?

This is clarifying re Harman's Object-Oriented Ontology:

REVIEW: THE THIRD TABLE

by Terence Blake

Review of Graham Harman's THE THIRD TABLE (Hatje Cantz, 2012)

This short brochure, THE THIRD TABLE, contains a concise overview of the central themes of Graham Harman's object-oriented philosophy, in a bilingual English-German edition. The English text occupies just eleven and a half pages (p4-15). The content is quite engaging as he manages to expound his ideas in the form of a response to Sir Arthur Eddington’s famous two table argument,which can be found in the introduction to his book THE NATURE OF THE PHYSICAL WORLD, first published in 1928. This argument famously contrasts the solid, substantial, reliable table of common sense with the insubstantial swarm of particles moving rapidly in what is mostly empty space that constitutes the table as modern physics envisages it. This allows Harman to couch his arguments in terms of a running engagement with reductionism, in what Harman sees as its humanistic and scientistic forms. So far so good. Problems arise however when we consider his account of each of Eddington’s two tables, and even more so with his presentation of the eponymous "third table".

1) THE FIRST TABLE: On Analogical Typology

THE THIRD TABLE does not give us a close reading of Eddington’s 1928 “Introduction”, nor does it intend to. It’s stake lies elsewhere, in a typological reading. From the “Introduction” Harman extracts two ideal types, the everyday table and the scientific one, and he immediately puts them in parallel with C.P. Snow’s famous distinction between the two cultures, the sciences and the humanities, “distinguishing”, according to Harman (p5), “so-called literary intellectuals from natural scientists”. (One may ask why the literary intellectuals merit the appellation “so-called”, but not the natural scientists. There would seem to be a residue of scientism that creeps into Harman’s exposition from time to time, even when he is describing his two adversaries). This is a bold leap of the analogical imagination, but unfortunately in this case it leads him astray. For the everyday table is not the table of the humanities (whatever that is!). For example, Proust’s table, a locus of intense and meaningful events, is not the everyday table. I am obliged here to hypothesise that literature belongs to the humanities, as Harman himself distinguishes the humanities from the arts, which are capable of rising to, or descending to (depending on your starting point), the Harmanian table, the “only real” table. He further complicates the matter by talking about the table being reducible “upward to a series of effects on people and other things”(p6). Now this is most strange, as Eddington insists on the substantiality of the everyday table, its solidity and compaction. The familiar table is all of a piece, and certainly not a “series of effects”, even less a series of “table-effects on humans”, as Harman would have it (p7). So the first table, the"familiar" one, in Harman's retelling has become a blurry composite somewhere between the everyday table, the table of the humanities, and the “series of effects” – with Harman sliding glibly from one to the other as if it were all the same to him. What seems to guide some of the slippage is the needs of the analogical argument, now favorising one term in the typological couple, now another. But a basic incertitude reigns as to the identity of the first table, at least in Harman’s text (for Eddington, as we have seen, there is no uncertainty). Harman has a real architectonic ambition, and, if only for this, he deserves our admiration and encouragement. But the typological imagination, with its bold analogical heuristics, can sometimes play tricks on even the best of us.

2) THE SECOND TABLE: On Reduction

The problem is that Harman seems to have no clear idea of what

reduction is. In effect, he presents us with an epistemological straw man supposed to exemplify the reductionism of modern physics. While ostensibly talking about Eddington’s parable of the two tables, Harman condemns the

procedure of the “scientist” who, according to him, “reduces the table downward to tiny particles invisible to the eye” (THE THIRD TABLE, p6), “dissolved into rushing electric charges and other tiny elements”. He contrasts this obviously unsatisfactory procedure of reduction with the Object-Oriented Philosopher’s respect for “the autonomous reality” of the table “over and above its causal components” (p7-8). He informs us that the table is an emergent whole which “has features that its various component particles do not have in isolation” (p7). This is an important point to make, but certainly not to Eddington or to any other physicist worthy of the name. Perhaps Harman is thinking in fact of Badiou and his set-theoretic reductionism, as he further declares that “objects are not just sets

of atoms” (p8, emphasis mine). However, for any real physicist a table is an emergent structure of particles and fields of force (not just electromagnetic but also gravitational and those of the weak and strong forces) and space-time. Even Eddington speaks of the table as composed of “space pervaded … by fields of force”, “electric charges rushing about with great speed”. Harman is wrong, in my opinion, to treat these “electric charges” as if they were just particles, and he pays no attention to the mention of speed. True, Eddington does talk as well of “electric particles”, but there is a progression in the text over the notion of these particles, from which he first removes all substance (p.xvi), and which he then terms “nuclei of electric force”(p.xvii), to finally declare the notion of a particle, such as an electron, too coloured by concretistic picture thinking and needing to be replaced by mathematical symbolism: “I can well understand that the younger minds are finding these pictures too concrete and are striving to construct the world out of Hamiltonian functions and symbols so far removed from human preconception that they do not even obey the laws of orthodox arithmetic” (p.xviii). Thus, contrary to what Harman asserts, there is no “reduction to tiny particles”, but a redescription in terms of a complex, emergent, structure of forces and fields and regions of space-time. I think Harman confuses reduction between different worlds with reduction inside a particular world. If scientists declared that the physicist’s table was the only real table, as Harman does with his philosophical table (he calls his third table, which can neither be known nor touched, “the only real one”) then that would be a form of reductionism. But we have seen that there is no reduction of the table to a set of tiny particles (how big is a field of force? how far does it extend? Harman is so obsessed with refuting a non-existent particle-reductionism that he does not consider these questions, and goes on to protest against an imaginary “prejudice” that maintains that “only the smallest things are real” (p8). This is precisely the picture-thinking that Eddington is eager to dispel in the physicist’s world). There is no “disintegrating” of the table into nothing but tiny electric charges or material flickerings” (p10). There is no “scientific dissolution” (p8) of the table into its component atoms, as this would be merely be bad science. To this extent, Harman’s new object-oriented ontology is just bad epistemology.

3) HARMAN'S "THIRD" TABLE

We have seen that Harman’s confusion over the nature of reduction leads him to misrepresent Eddington’s explication of the physicist’s table. Harman has centered THE THIRD TABLE on a critique of the two tables described by Eddington, as products of “reduction downward” (the physicist’s table) and of “reduction upward” (the everyday table) respectively. These terms seem to be the equivalents of what he elsewhere (e.g. in THE QUADRUPLE OBJECT) calls "undermining"and "overmining". Reducing the table to particles (which, as I have shown, Eddington does not) would correspond to undermining, and reducing it to its effects on human subjects (neither does he do this) would be overmining. Thus Harman's master argument for introducing his so-called"real object" (the third table) to save us from reductionism fails.

4) ETHICS AND OBJECTS: love the table

Harman situates his third table in an epistemological space, under the everyday table (or is it the humanist’s table? or the bundle-of-effects-on-humans table? Harman, as we have seen does not clearly distinguish between these variants in the pursuit of his argument) and above the scientific table: “By locating the third table (and to repeat, this is the only real table) in a space between the “table”as particles and the “table” in its effects on humans, we have apparently found a table that can be verified in no way at all … Yes, and that is precisely the point” (p11-12). The table is not just untouchable, it is also unverifiable, which in Harman’s epistemology seems to mean that it is unknowable, as he adds “The real is something that cannot be known, only loved”(p12). Loving the table is to be understood in terms of the “erotic model” (15), whose principal feature seems to be indirectness and obliquity. Many have talked about reinstating an erotic knowledge of objects, of unifying eros and logos. I am all in favour of this idea, and I think the work of the Scottish poet Kenneth White is [sic] gives us many useful indications of what such an erotic model entails. But these thinkers typically advocate a sensual encounter with objects in their singularity, and Harman emphasises rather the non-sensual withdrawal of his intelligible objects. For they are intelligible and not sensible, not touchable, not verifiable, not knowable. We are deep in negative theology country here, far from the familiar objects of everyday life. Negative theology does not in itself constitute a problem, unconsciously pursuing a naïve and dogmatic form of negative theology does.

5) CONCLUSION

The desire to escape from enslavement to traditional transcendental schemas of conceptuality, to be free from the domination of transcendence and of onto-theology, to make the leap into pure immanence, explains why one can be attracted by the pretentions of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) to embody a non-traditional or non-standard philosophy. There is in OOO a promise of such a leap out of the old transcendental structures and into immanence, out of onto-theology and into a negative theology, in the strong intensive sense of “negative” which would take it outside theology and into a non-theology and a non-philosophy, take it outside of the mind and its stratified concepts into the plurality and the flux of immanence. My critique of OOO is not so much that it is negative theology, but that it is bad negative theology, a new impoverishment and imprisonment of the spirit, and remains blind to its theological underpinnings. A comparison with the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend can help us see the shortcomings of Harman's OOO more clearly. Feyerabend freely acknowledges his theological inspiration in his notion of the Real. He says explicitly “I myself have started from what Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita said about the names of God” (CONQUEST OF ABUNDANCE, 195). He also calls his point of view a form of “mysticism with arguments” (“a mysticism that uses examples, arguments, tightly reasoned passages of text, scientific theories and experiments to raise itself into consciousness”). Feyerabend had much in common with the motivations of OOO but he went much further in getting us to “regard any clear and definite arrangement with suspicion” (letter -preface to AGAINST METHOD). This suspicion is like the “non-” of non-philosophy, it does not negate the clear and definite structures and schemas, nor does it become the basis of a new negative philosophy: “It is very important not to let this suspicion deteriorate into a truth, or a theory, for example into a theory with the principle: things are never what they seem to be. Reality, or Being, or God, or whatever it is that sustains us cannot be captured that easily”.

So a liberation from the limiting conceptual schemas of philosophy is possible if, as Feyerabend invites us, we think and act outside stable frameworks (“There are many ways and we are using them all the time though often believing that they are part of a stable framework which encompasses everything”) and fixed paths (“Is argument without a purpose? No, it is not; it accompanies us on our journey without tying it to a fixed road”). This is what one could call a“diachronic ontology”. It is the exact opposite of the path that OOO has chosen, where we find increasingly no mysticism and no arguments.

REVIEW Of GRAHAM HARMAN’S “THE THIRD TABLE” | AGENT SWARM

REVIEW: THE THIRD TABLE

by Terence Blake

Review of Graham Harman's THE THIRD TABLE (Hatje Cantz, 2012)

This short brochure, THE THIRD TABLE, contains a concise overview of the central themes of Graham Harman's object-oriented philosophy, in a bilingual English-German edition. The English text occupies just eleven and a half pages (p4-15). The content is quite engaging as he manages to expound his ideas in the form of a response to Sir Arthur Eddington’s famous two table argument,which can be found in the introduction to his book THE NATURE OF THE PHYSICAL WORLD, first published in 1928. This argument famously contrasts the solid, substantial, reliable table of common sense with the insubstantial swarm of particles moving rapidly in what is mostly empty space that constitutes the table as modern physics envisages it. This allows Harman to couch his arguments in terms of a running engagement with reductionism, in what Harman sees as its humanistic and scientistic forms. So far so good. Problems arise however when we consider his account of each of Eddington’s two tables, and even more so with his presentation of the eponymous "third table".

1) THE FIRST TABLE: On Analogical Typology

THE THIRD TABLE does not give us a close reading of Eddington’s 1928 “Introduction”, nor does it intend to. It’s stake lies elsewhere, in a typological reading. From the “Introduction” Harman extracts two ideal types, the everyday table and the scientific one, and he immediately puts them in parallel with C.P. Snow’s famous distinction between the two cultures, the sciences and the humanities, “distinguishing”, according to Harman (p5), “so-called literary intellectuals from natural scientists”. (One may ask why the literary intellectuals merit the appellation “so-called”, but not the natural scientists. There would seem to be a residue of scientism that creeps into Harman’s exposition from time to time, even when he is describing his two adversaries). This is a bold leap of the analogical imagination, but unfortunately in this case it leads him astray. For the everyday table is not the table of the humanities (whatever that is!). For example, Proust’s table, a locus of intense and meaningful events, is not the everyday table. I am obliged here to hypothesise that literature belongs to the humanities, as Harman himself distinguishes the humanities from the arts, which are capable of rising to, or descending to (depending on your starting point), the Harmanian table, the “only real” table. He further complicates the matter by talking about the table being reducible “upward to a series of effects on people and other things”(p6). Now this is most strange, as Eddington insists on the substantiality of the everyday table, its solidity and compaction. The familiar table is all of a piece, and certainly not a “series of effects”, even less a series of “table-effects on humans”, as Harman would have it (p7). So the first table, the"familiar" one, in Harman's retelling has become a blurry composite somewhere between the everyday table, the table of the humanities, and the “series of effects” – with Harman sliding glibly from one to the other as if it were all the same to him. What seems to guide some of the slippage is the needs of the analogical argument, now favorising one term in the typological couple, now another. But a basic incertitude reigns as to the identity of the first table, at least in Harman’s text (for Eddington, as we have seen, there is no uncertainty). Harman has a real architectonic ambition, and, if only for this, he deserves our admiration and encouragement. But the typological imagination, with its bold analogical heuristics, can sometimes play tricks on even the best of us.

2) THE SECOND TABLE: On Reduction

The problem is that Harman seems to have no clear idea of what

reduction is. In effect, he presents us with an epistemological straw man supposed to exemplify the reductionism of modern physics. While ostensibly talking about Eddington’s parable of the two tables, Harman condemns the

procedure of the “scientist” who, according to him, “reduces the table downward to tiny particles invisible to the eye” (THE THIRD TABLE, p6), “dissolved into rushing electric charges and other tiny elements”. He contrasts this obviously unsatisfactory procedure of reduction with the Object-Oriented Philosopher’s respect for “the autonomous reality” of the table “over and above its causal components” (p7-8). He informs us that the table is an emergent whole which “has features that its various component particles do not have in isolation” (p7). This is an important point to make, but certainly not to Eddington or to any other physicist worthy of the name. Perhaps Harman is thinking in fact of Badiou and his set-theoretic reductionism, as he further declares that “objects are not just sets

of atoms” (p8, emphasis mine). However, for any real physicist a table is an emergent structure of particles and fields of force (not just electromagnetic but also gravitational and those of the weak and strong forces) and space-time. Even Eddington speaks of the table as composed of “space pervaded … by fields of force”, “electric charges rushing about with great speed”. Harman is wrong, in my opinion, to treat these “electric charges” as if they were just particles, and he pays no attention to the mention of speed. True, Eddington does talk as well of “electric particles”, but there is a progression in the text over the notion of these particles, from which he first removes all substance (p.xvi), and which he then terms “nuclei of electric force”(p.xvii), to finally declare the notion of a particle, such as an electron, too coloured by concretistic picture thinking and needing to be replaced by mathematical symbolism: “I can well understand that the younger minds are finding these pictures too concrete and are striving to construct the world out of Hamiltonian functions and symbols so far removed from human preconception that they do not even obey the laws of orthodox arithmetic” (p.xviii). Thus, contrary to what Harman asserts, there is no “reduction to tiny particles”, but a redescription in terms of a complex, emergent, structure of forces and fields and regions of space-time. I think Harman confuses reduction between different worlds with reduction inside a particular world. If scientists declared that the physicist’s table was the only real table, as Harman does with his philosophical table (he calls his third table, which can neither be known nor touched, “the only real one”) then that would be a form of reductionism. But we have seen that there is no reduction of the table to a set of tiny particles (how big is a field of force? how far does it extend? Harman is so obsessed with refuting a non-existent particle-reductionism that he does not consider these questions, and goes on to protest against an imaginary “prejudice” that maintains that “only the smallest things are real” (p8). This is precisely the picture-thinking that Eddington is eager to dispel in the physicist’s world). There is no “disintegrating” of the table into nothing but tiny electric charges or material flickerings” (p10). There is no “scientific dissolution” (p8) of the table into its component atoms, as this would be merely be bad science. To this extent, Harman’s new object-oriented ontology is just bad epistemology.

3) HARMAN'S "THIRD" TABLE

We have seen that Harman’s confusion over the nature of reduction leads him to misrepresent Eddington’s explication of the physicist’s table. Harman has centered THE THIRD TABLE on a critique of the two tables described by Eddington, as products of “reduction downward” (the physicist’s table) and of “reduction upward” (the everyday table) respectively. These terms seem to be the equivalents of what he elsewhere (e.g. in THE QUADRUPLE OBJECT) calls "undermining"and "overmining". Reducing the table to particles (which, as I have shown, Eddington does not) would correspond to undermining, and reducing it to its effects on human subjects (neither does he do this) would be overmining. Thus Harman's master argument for introducing his so-called"real object" (the third table) to save us from reductionism fails.

4) ETHICS AND OBJECTS: love the table

Harman situates his third table in an epistemological space, under the everyday table (or is it the humanist’s table? or the bundle-of-effects-on-humans table? Harman, as we have seen does not clearly distinguish between these variants in the pursuit of his argument) and above the scientific table: “By locating the third table (and to repeat, this is the only real table) in a space between the “table”as particles and the “table” in its effects on humans, we have apparently found a table that can be verified in no way at all … Yes, and that is precisely the point” (p11-12). The table is not just untouchable, it is also unverifiable, which in Harman’s epistemology seems to mean that it is unknowable, as he adds “The real is something that cannot be known, only loved”(p12). Loving the table is to be understood in terms of the “erotic model” (15), whose principal feature seems to be indirectness and obliquity. Many have talked about reinstating an erotic knowledge of objects, of unifying eros and logos. I am all in favour of this idea, and I think the work of the Scottish poet Kenneth White is [sic] gives us many useful indications of what such an erotic model entails. But these thinkers typically advocate a sensual encounter with objects in their singularity, and Harman emphasises rather the non-sensual withdrawal of his intelligible objects. For they are intelligible and not sensible, not touchable, not verifiable, not knowable. We are deep in negative theology country here, far from the familiar objects of everyday life. Negative theology does not in itself constitute a problem, unconsciously pursuing a naïve and dogmatic form of negative theology does.

5) CONCLUSION

The desire to escape from enslavement to traditional transcendental schemas of conceptuality, to be free from the domination of transcendence and of onto-theology, to make the leap into pure immanence, explains why one can be attracted by the pretentions of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) to embody a non-traditional or non-standard philosophy. There is in OOO a promise of such a leap out of the old transcendental structures and into immanence, out of onto-theology and into a negative theology, in the strong intensive sense of “negative” which would take it outside theology and into a non-theology and a non-philosophy, take it outside of the mind and its stratified concepts into the plurality and the flux of immanence. My critique of OOO is not so much that it is negative theology, but that it is bad negative theology, a new impoverishment and imprisonment of the spirit, and remains blind to its theological underpinnings. A comparison with the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend can help us see the shortcomings of Harman's OOO more clearly. Feyerabend freely acknowledges his theological inspiration in his notion of the Real. He says explicitly “I myself have started from what Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita said about the names of God” (CONQUEST OF ABUNDANCE, 195). He also calls his point of view a form of “mysticism with arguments” (“a mysticism that uses examples, arguments, tightly reasoned passages of text, scientific theories and experiments to raise itself into consciousness”). Feyerabend had much in common with the motivations of OOO but he went much further in getting us to “regard any clear and definite arrangement with suspicion” (letter -preface to AGAINST METHOD). This suspicion is like the “non-” of non-philosophy, it does not negate the clear and definite structures and schemas, nor does it become the basis of a new negative philosophy: “It is very important not to let this suspicion deteriorate into a truth, or a theory, for example into a theory with the principle: things are never what they seem to be. Reality, or Being, or God, or whatever it is that sustains us cannot be captured that easily”.

So a liberation from the limiting conceptual schemas of philosophy is possible if, as Feyerabend invites us, we think and act outside stable frameworks (“There are many ways and we are using them all the time though often believing that they are part of a stable framework which encompasses everything”) and fixed paths (“Is argument without a purpose? No, it is not; it accompanies us on our journey without tying it to a fixed road”). This is what one could call a“diachronic ontology”. It is the exact opposite of the path that OOO has chosen, where we find increasingly no mysticism and no arguments.

REVIEW Of GRAHAM HARMAN’S “THE THIRD TABLE” | AGENT SWARM

By way if contrast to Evans cf Dummett's book 'The seas of language' Chapter "what is a theory of meaning (I)" first couple of pages.

Thanks very much for that reference. I was going to ask you for an approach to contrast with Evans's.

@Constance re the B&T review... interesting I thought, the reference to theology and Christianity

Apropos of that, read the review of the pamphlet on OOO by Graham Harman posted just above.

ps: there's something for all of us there.

Last edited:

Soupie

Paranormal Adept

@Soupie: It's not easy for me to see how qualia or whole minds could be fundamental.

I don’t think so. Why do you ask?

I think of a brain as a physical, objective structure/process. And while the general, global structure/processes of an individual brain are fairly stable, they can and do change over time. While locally, a living brain is constantly changing.

Perhaps an analog would be a city; a living city is full of constant movement and change, but globally it’s structure/processes remain fairly stable; however, cities can and do undergo large, global changes as well.

I have come to think of the mind as the quasi-physical, subjective, (intentional) information embodied by the brain. If the brain can be said to be dynamic, the information it embodies is even more so. However, just as some structures/processes of the brain remain stable over time, so too can some of the information it carries.

I don’t think of the brain as a digital computer that is computing the mind. Nor do I think of the mind as a digital program that is running on the brain.

But I do think of the mind as information that is embodied by physical processes in the body/brain.

Finally, I cannot answer why some of the information embodied by the brain at any given time feels like something, and why some does not.

It seems that typically our (phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual) conscious awareness is spun into a not-so-accurate, ongoing narrative of what it's like to be.

There are exactly zero models to account for how and why this conscious narrative phenomena exists. Amazing.

I don't know that there is "part" of a mind. However, there are many, many accounts of brain insult, injury, or illness which lead to individuals with once "whole" minds, losing which is essentially "part" of their mind.

I understand that you want to resist thinking of consciousness in physical terms. However, if protoconsciousness exists, it's possible that it can be combined, shaped, and/or filtered in such a way that differentiated qualia emerge. Perhaps not unlike a host of various colors emerging from a few primary colors.

If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass), then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

I don’t think so. Why do you ask?

I think of a brain as a physical, objective structure/process. And while the general, global structure/processes of an individual brain are fairly stable, they can and do change over time. While locally, a living brain is constantly changing.

Perhaps an analog would be a city; a living city is full of constant movement and change, but globally it’s structure/processes remain fairly stable; however, cities can and do undergo large, global changes as well.

I have come to think of the mind as the quasi-physical, subjective, (intentional) information embodied by the brain. If the brain can be said to be dynamic, the information it embodies is even more so. However, just as some structures/processes of the brain remain stable over time, so too can some of the information it carries.

I don’t think of the brain as a digital computer that is computing the mind. Nor do I think of the mind as a digital program that is running on the brain.

But I do think of the mind as information that is embodied by physical processes in the body/brain.

Finally, I cannot answer why some of the information embodied by the brain at any given time feels like something, and why some does not.

It seems that typically our (phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual) conscious awareness is spun into a not-so-accurate, ongoing narrative of what it's like to be.

There are exactly zero models to account for how and why this conscious narrative phenomena exists. Amazing.

2. is there such a thing as part of a mind? if not ... at what point does it become a mind? (emergence)

I don't know that there is "part" of a mind. However, there are many, many accounts of brain insult, injury, or illness which lead to individuals with once "whole" minds, losing which is essentially "part" of their mind.

3. if qualia isn't fundamental, then something entirely novel has to emerge ... how do we account for that? is emergence fundamental?

I understand that you want to resist thinking of consciousness in physical terms. However, if protoconsciousness exists, it's possible that it can be combined, shaped, and/or filtered in such a way that differentiated qualia emerge. Perhaps not unlike a host of various colors emerging from a few primary colors.

If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass), then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

4. if we think of brains as networks that filter or move consciousness around, then we are picturing consciousness as a field or a fluid, would it be possible then to empty a brain of this field or fluid? Sometimes this field or fluid is called "information" there the picture is that somehow the electro-chemical "signals" (which are also a kind of fluid) give rise to (emergence) information/consciousness, it leaks or bubbles up out of electricity and chemistry and then this whole thing is moved around in the brain to produce "what it is like". I think such pictures stand behind our mainstream concept of the briain and are very misleading.

Another way to think about "what it is like" is to think that when I look at the sun, there is something it is like for me and the sun to be in a relationship of looking and being looked at that is not contained inside my skull.

The way I think about this is to try not to use metaphors or images. Think only with the words - this is what people gripe about with mystical writing because it leads to paradox or (non)-sense. That may be OK - Zeno's Paradox is non-sense but leads to the idea of limits which is fundamental to Calculus. There may not be a physics of consciousness, we may not be able to move from object to subject continuously - if so, this argues against a physicalist view of the world.

The bone boundary of the skull is what demaractes these two philosophies, nicht wahr?

If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass), . . .

Except, as Panksepp has pointed out, the seeds of protoconsciousness have germinated before neurons have evolved in the evolution of living organisms, revealed in the 'affectivity' and 'seeking behavior' recognizable in primordial organisms and, indeed, even in the earliest single-celled organism observed and described by Maturana and Varela and termed 'autopoiesis'.

. . . then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

Neurons just do that because they can? What motivates these neuronal pyrotechniques? Our neurons do not produce our experiences in and of the world, they respond to them, organize and integrate them, facilitate our responses to what happens. The brain facilitates consciousness and mind, which originate in our interactions with our actual surrounding environment. At every stage of the evolution of species, an organism's lived experience in the world expands its awareness of itself and its mileau.

S

smcder

Guest

This is clarifying re Harman's Object-Oriented Ontology:

REVIEW: THE THIRD TABLE

by Terence Blake

Review of Graham Harman's THE THIRD TABLE (Hatje Cantz, 2012)

...

So a liberation from the limiting conceptual schemas of philosophy is possible if, as Feyerabend invites us, we think and act outside stable frameworks (“There are many ways and we are using them all the time though often believing that they are part of a stable framework which encompasses everything”) and fixed paths (“Is argument without a purpose? No, it is not; it accompanies us on our journey without tying it to a fixed road”). This is what one could call a“diachronic ontology”. It is the exact opposite of the path that OOO has chosen, where we find increasingly no mysticism and no arguments.

REVIEW Of GRAHAM HARMAN’S “THE THIRD TABLE” | AGENT SWARM

Here are a couple of responses I found to this ... the first is more generally on the analytic/continental split and the internecine warfare I sensed might lie behind Blake's review ... the second is a 2013 response to Blake from Harmon:

How not to to engage with other humanists; Nathan Brown and the continental/continental divide - New APPS: Art, Politics, Philosophy, Science

terence blake | Search Results | Object-Oriented Philosophy

I also did a search in Harmon's blog for "Terence Blake" and found just a few entries, but they are worth reading.

S

smcder

Guest

Steven Shaviro--Other Writings

book reviews, articles, other writings

includes a scholarly article entitled "the universe of things" as PDF

book reviews, articles, other writings

includes a scholarly article entitled "the universe of things" as PDF

S

smcder

Guest

Human, All Too Human

HUMAN, ALL TOO HUMAN:

Kismet and the Problem of Machine Emotions

Steven Shaviro

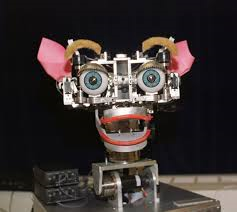

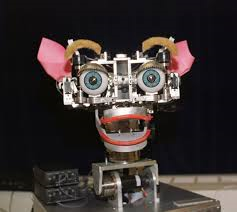

Kismet is a robot, "designed for social interactions with humans," made by Cynthia Breazeal at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab. In appearance, Kismet is something like a cartoon head, realized in the form of a 3D metal-and-plastic sculpture, and come disconcertingly to life. Kismet has comically large eyebrows arching over big round eyes, extended flappable (but not quite floppy) ears, and a broad metallic mouth with curling lips. By moving its various parts, Kismet is able to make a variety of facial "expressions." These signify different "emotions" and "expressive states," ranging from happiness and calm, to disgust, anger, and fear. But no matter what "mood" Kismet is in, it is almost unbearably cute, like a cross between Barney the Purple Dinosaur and Disney's Country Bear Jamboree.

...

The recognition by AI researchers that mental activity is emotional and embodied, and not merely a matter of logical reasoning, is certainly a welcome step forward. But I continue to wonder about the underlying assumptions that drive these projects. What view of emotion is being put to work here?

The theory, I think, goes something like this.

In a similar vein, I am inclined to say that human beings do not work to rationally maximize their utility; only economists and computer engineers do.

For the "rational choice" view leaves out everything that goes beyond subsistence and reproduction; everything, that is, that makes life interesting. It leaves no room for all those feelings, gestures, and behaviors that are whimsical, impulsive, arbitrary, imaginative, obsessive, beautiful, or otherwise excessive. In short, it leaves out love, poetry, and madness, together with all else that makes for the richness, diversity, and unpredictability of human culture.

That is why, despite the recent changes in AI research, I still do not expect too much from Cog, Kismet, and their kin. As an engineering achievement, Kismet is brilliant. But as an experiment in human/machine interaction, it is really just more of the same. The video of Breazeal playing with Kismet tells me why. The (male) voiceover explanation of how Kismet works has the didactic, omniscient tone of a 1950s instructional film. And as Breazeal waves the stuffed cow in the robot's face, she seems to be playing Mom with the forcibly cheery affect of a family sitcom from the same period. It would seem, then, that Kismet is modeled not so much, as Breazeal claims, on "the way infants learn to communicate with adults," as it is on a much more particular fantasy: that of the earnest, well-adjusted, white, middle-class, suburban American child. For all the recent talk of "how we became posthuman" (to cite the title of a recent book by Katherine Hayles), it would seem that we are fated to get back from computers only what we put into them in the first place.

HUMAN, ALL TOO HUMAN:

Kismet and the Problem of Machine Emotions

Steven Shaviro

Kismet is a robot, "designed for social interactions with humans," made by Cynthia Breazeal at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab. In appearance, Kismet is something like a cartoon head, realized in the form of a 3D metal-and-plastic sculpture, and come disconcertingly to life. Kismet has comically large eyebrows arching over big round eyes, extended flappable (but not quite floppy) ears, and a broad metallic mouth with curling lips. By moving its various parts, Kismet is able to make a variety of facial "expressions." These signify different "emotions" and "expressive states," ranging from happiness and calm, to disgust, anger, and fear. But no matter what "mood" Kismet is in, it is almost unbearably cute, like a cross between Barney the Purple Dinosaur and Disney's Country Bear Jamboree.

...

The recognition by AI researchers that mental activity is emotional and embodied, and not merely a matter of logical reasoning, is certainly a welcome step forward. But I continue to wonder about the underlying assumptions that drive these projects. What view of emotion is being put to work here?

The theory, I think, goes something like this.

- The robot, like a biological organism, is assumed to have a fixed number of underlying drives. These drives refer to conditions that the organism tries to fulfill, within the limits of homeostatic equilibrium.

- Fulfillment of the conditions of these drives-having a good meal in good company-leads to satisfaction. Either too little or too much stimulation of the drives-starvation on the one hand, or an ancient Roman banquet on the other-leads, instead, to dissatisfaction. These states of satisfaction and dissatisfaction are then expressed in the form of emotions.

- Such an account is pretty much the standard one in cognitive science today. It's an instrumentalized view of "human nature" that ultimately derives from what is known as "rational choice" theory in economics and political science. This is the idea that all human behavior can be explained by the assumption that each individual acts so as to maximize his or her utility. Under this theory, human beings need not actually be rational; they still pursue their goals as if they were rational. Emotion is not denied; but it is relegated to being only a tool that helps the individual to efficiently accomplish his or her goals. Everything is supposed to work out correctly, thanks to an updated version of Adam Smith's "invisible hand." Models derived from economic competition in the marketplace are used by social scientists like Nobel Prize winner Gary Becker to explain all sorts of things, from family dynamics to drug addiction and crime to voting and political activism.

- this approach has not just gained a foothold in universities and public-policy think tanks. It has also filtered down into the popular imagination, in much the way that Freudianism did fifty years ago. And it has become ubiquitous in recent computer engineering work, not just in AI and robotics research, but also in interface design and interactive games.

In a similar vein, I am inclined to say that human beings do not work to rationally maximize their utility; only economists and computer engineers do.

For the "rational choice" view leaves out everything that goes beyond subsistence and reproduction; everything, that is, that makes life interesting. It leaves no room for all those feelings, gestures, and behaviors that are whimsical, impulsive, arbitrary, imaginative, obsessive, beautiful, or otherwise excessive. In short, it leaves out love, poetry, and madness, together with all else that makes for the richness, diversity, and unpredictability of human culture.

That is why, despite the recent changes in AI research, I still do not expect too much from Cog, Kismet, and their kin. As an engineering achievement, Kismet is brilliant. But as an experiment in human/machine interaction, it is really just more of the same. The video of Breazeal playing with Kismet tells me why. The (male) voiceover explanation of how Kismet works has the didactic, omniscient tone of a 1950s instructional film. And as Breazeal waves the stuffed cow in the robot's face, she seems to be playing Mom with the forcibly cheery affect of a family sitcom from the same period. It would seem, then, that Kismet is modeled not so much, as Breazeal claims, on "the way infants learn to communicate with adults," as it is on a much more particular fantasy: that of the earnest, well-adjusted, white, middle-class, suburban American child. For all the recent talk of "how we became posthuman" (to cite the title of a recent book by Katherine Hayles), it would seem that we are fated to get back from computers only what we put into them in the first place.

S

smcder

Guest

following up on Kismet, I found Cynthia Brazeal's current Indi-gogo project, JIBO

"The World's First Social Robot for the Home"

JIBO, The Worlds First Social Robot for the Home | Indiegogo

"The World's First Social Robot for the Home"

JIBO, The Worlds First Social Robot for the Home | Indiegogo

S

smcder

Guest

@Soupie: It's not easy for me to see how qualia or whole minds could be fundamental.

I don’t think so. Why do you ask?

I think of a brain as a physical, objective structure/process. And while the general, global structure/processes of an individual brain are fairly stable, they can and do change over time. While locally, a living brain is constantly changing.

Perhaps an analog would be a city; a living city is full of constant movement and change, but globally it’s structure/processes remain fairly stable; however, cities can and do undergo large, global changes as well.

I have come to think of the mind as the quasi-physical, subjective, (intentional) information embodied by the brain. If the brain can be said to be dynamic, the information it embodies is even more so. However, just as some structures/processes of the brain remain stable over time, so too can some of the information it carries.

I don’t think of the brain as a digital computer that is computing the mind. Nor do I think of the mind as a digital program that is running on the brain.

But I do think of the mind as information that is embodied by physical processes in the body/brain.

Finally, I cannot answer why some of the information embodied by the brain at any given time feels like something, and why some does not.

It seems that typically our (phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual) conscious awareness is spun into a not-so-accurate, ongoing narrative of what it's like to be.

There are exactly zero models to account for how and why this conscious narrative phenomena exists. Amazing.

I don't know that there is "part" of a mind. However, there are many, many accounts of brain insult, injury, or illness which lead to individuals with once "whole" minds, losing which is essentially "part" of their mind.

I understand that you want to resist thinking of consciousness in physical terms. However, if protoconsciousness exists, it's possible that it can be combined, shaped, and/or filtered in such a way that differentiated qualia emerge. Perhaps not unlike a host of various colors emerging from a few primary colors.

If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass), then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

http://shaviro.com/Othertexts/Claremont2010.pdf

Good primer/refresher on panpsychism by Shaviro, it seems to contrast with your view which appears to be the standard physicalist/emergent position - allowing for information to be "quasi" (do you mean "semi" instead?) physical and intentional ... short of that, I'm not sure it's really panpsychism, you don't have room for mind/mentality/experience/qualia to be fundamental ...

the combination problem nervous systems and brains develop under biological/chemical/physical constraints and so the combination problem involves that the structure of the brain, so constrained, still coincides with the "structure" of the mind - but this gives up the advantages of panpsychism, of mind being fundamental, so that it's very hard not to have a "psycho-physical nexus" or not to think in terms electrity:wires software:computer ... even though you disclaim this, your model looks an awful lot like that ... (if not, what metaphor would you use to describe the brain/mind relationship? I think you've used excreted or generated?)

a different way would be to think of mindedness as truly fundamental, so that the nervous system enables a body to move around in space and with purpose in the sense that the physical acts are accompanied by fundamental mental states like intention and meaning ... this also matches some of the empirical data that seems to say the hand moves as or just before the intention ... the intention then feeding back into the movement ...

perhaps

http://shaviro.com/Othertexts/Claremont2010.pdf

Last edited by a moderator:

S

smcder

Guest

@Soupie: It's not easy for me to see how qualia or whole minds could be fundamental.

I don’t think so. Why do you ask?

I think of a brain as a physical, objective structure/process. And while the general, global structure/processes of an individual brain are fairly stable, they can and do change over time. While locally, a living brain is constantly changing.

Perhaps an analog would be a city; a living city is full of constant movement and change, but globally it’s structure/processes remain fairly stable; however, cities can and do undergo large, global changes as well.

I have come to think of the mind as the quasi-physical, subjective, (intentional) information embodied by the brain. If the brain can be said to be dynamic, the information it embodies is even more so. However, just as some structures/processes of the brain remain stable over time, so too can some of the information it carries.

I don’t think of the brain as a digital computer that is computing the mind. Nor do I think of the mind as a digital program that is running on the brain.

But I do think of the mind as information that is embodied by physical processes in the body/brain.

Finally, I cannot answer why some of the information embodied by the brain at any given time feels like something, and why some does not.

It seems that typically our (phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual) conscious awareness is spun into a not-so-accurate, ongoing narrative of what it's like to be.

There are exactly zero models to account for how and why this conscious narrative phenomena exists. Amazing.

I don't know that there is "part" of a mind. However, there are many, many accounts of brain insult, injury, or illness which lead to individuals with once "whole" minds, losing which is essentially "part" of their mind.

I understand that you want to resist thinking of consciousness in physical terms. However, if protoconsciousness exists, it's possible that it can be combined, shaped, and/or filtered in such a way that differentiated qualia emerge. Perhaps not unlike a host of various colors emerging from a few primary colors.

If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass), then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass),

then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind

I myself can't see how this happens ... how something of a different order altogether (experience) arises from electro-chemical interactions. And I don't think you can see it either, I think you are simply claim it - based on the idea of emergence, but emergence itself isn't something you can see or have any intuitions about - it's just a statement that more complex things come out of interactions according to simple rules.

If you do actually see this, then what imagery, what metaphor, what comparisons, what intuitions fo you have about it and can you make to something that we do know about?

Soupie

Paranormal Adept

@Soupie: If we assume that individual neurons, or perhaps small clusters of integrated neurons, are directly correlated to this protoconsciousness (the way a subatomic particle is correlated with mass), . . .

@Constance: Except, as Panksepp has pointed out, the seeds of protoconsciousness have germinated before neurons have evolved in the evolution of living organisms, revealed in the 'affectivity' and 'seeking behavior' recognizable in primordial organisms and, indeed, even in the earliest single-celled organism observed and described by Maturana and Varela and termed 'autopoiesis'.

Actually, I thought we determined that Panksepp’s “Affective Neuroscience” was indeed based on neurons?

From wiki:

“Affective neuroscience is the study of the neural mechanisms of emotion. This interdisciplinary field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood.[1]”

@Soupie: . . . then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

@Constance: Neurons just do that because they can? What motivates these neuronal pyrotechniques? Our neurons do not produce our experiences in and of the world, they respond to them, organize and integrate them, facilitate our responses to what happens. The brain facilitates consciousness and mind, which originate in our interactions with our actual surrounding environment. At every stage of the evolution of species, an organism's lived experience in the world expands its awareness of itself and its mileau.

@Soupie: What do you mean by “our experiences” in this context? If by our experiences, you mean our physical interaction with the world, then yes, I agree.

We are physical beings physically interacting with a physical world.

However, the question is, why are we subjects of phenomenal experience. Why does it feel like something to be physical beings physically interacting with the physical world?

So, I would make a distinction between our physical bodies having physical, causal “experiences” with the physical world, and the phenomenal, narrative experience that -- at least for humans -- accompanies our physical being in the world.

We don’t have an answer for why this phenomenal experiential narrative exists. We just don’t. However, when the brain -- and namely clusters of neurons -- is damaged, the stream/waves of phenomenal, feeling, something-it-is-like is effected. Hence, there’s seems to be some special relationship between neurons and consciousness. Just what that relationship is, we don’t know.

-----

@smcder: the combination problem nervous systems and brains develop under biological/chemical/physical constraints and so the combination problem involves that the structure of the brain, so constrained, still coincides with the "structure" of the mind - but this gives up the advantages of panpsychism, of mind being fundamental, so that it's very hard not to have a "psycho-physical nexus" or not to think in terms electrity:wires software:computer ... even though you disclaim this, your model looks an awful lot like that ... (if not, what metaphor would you use to describe the brain/mind relationship? I think you've used excreted or generated?)

@Soupie: Let’s say that Susan has not been born yet. On my approach, neither her brain nor her mind exists yet. (Never mind metaphysical questions about time, yada, yada.)

I think wherever there is matter (whatever that is) there is mental. So elementary particles (whatever they are) “carry” with them a mental property. This is fundamental.

[Now, what I’m not clear on, is whether particles are themselves a result of interaction and/or relationship. That is, if a particle is really the result of a relationship between X and Y, that means “fundamental” properties are also a result of this relationship. So in other words, when I use the term fundamental, I’m really just saying it’s something that just is, but we haven’t a clue why… like, why do matter, energy, and fields exist? We don’t know.]

So all matter has mental. But not all material structures/processes have minds, or at least minds like ours.

As you know, there is no metaphor that can capture the unique relationship of matter and mind. Using a metaphor about matter relating to matter will not capture matter relating to mind.

I do think the matter-information is the best metaphor (and I believe of course that it may be more than a metaphor).

I say that mental is a fundamental property of all matter, but that not all material structures have minds (like ours).

I can say that all material structures can be said to embody information (form), but that not all material structures embody information that constitutes a mind (like ours).

I think our bodies/brains embody intentional information. What is intentional information? It is information about something. What does this mean? It means one physical form is “about” another physical form.

So a beautiful picture of a woman is about a real woman. The picture embodies intentional information of the woman.

All interacting, fundamental particles by way of their interactions with one another can be said to carry information about one another.

Intentional information is everywhere. Experience is everywhere. Mental is everywhere. Panpsychism.

The human brain by way of neurons, embodies intentional information that has somehow become self-aware. So as Susan’s brain develops and grows, so too does the intentional information it embodies. If the brain is damaged, the mind is damaged.

The brain embodies intentional information (form) that is aware that it is about some other physical form. When we experience the sun, our physical body is being physically changed. When know that our experience of the sun is about something.

Our brain is a painting that is aware that it is a painting.

That is, I think consciousness can exist in-itself (the mind is green), but that consciousness can exist for-itself (I am seeing something green). I think what we experience as our conscious narrative is consciousness for-itself.

[However, as we know, one of the amazing things about quasi-physical information, is that it is substrate independent. It can travel from physical substrate to physical substrate. So my thoughts move from my brain to the actions of my fingers on my keyboard. The function of the keyboard causes software to encode my thoughts that I translated to words into binary code. This code travels as light through the interwebs onto Gene’s server. This code is then decoded and manifested as lighted pixels on your screens. That light is received by your retinas. Your retinas transduce this light into electrical pulses that travel on your optic nerves into your brains/neurons. You (read: not your neurons) then read/decode the words, and derive meaning from them.

This is all to say that I would still consider myself a dualist. I think the brain and the mind are distinct. There may be some circumstances wherein the human mind exists apart from the physical brain with which it was once associated.

@Constance: Except, as Panksepp has pointed out, the seeds of protoconsciousness have germinated before neurons have evolved in the evolution of living organisms, revealed in the 'affectivity' and 'seeking behavior' recognizable in primordial organisms and, indeed, even in the earliest single-celled organism observed and described by Maturana and Varela and termed 'autopoiesis'.

Actually, I thought we determined that Panksepp’s “Affective Neuroscience” was indeed based on neurons?

From wiki:

“Affective neuroscience is the study of the neural mechanisms of emotion. This interdisciplinary field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood.[1]”

@Soupie: . . . then it's not hard for me to see how a truly vast system of billions of neurons firing, spiking, communicating, feeding back, and synchronizing together might give rise to a rich array of phenomenal, emotional, and conceptual qualia that comprise the conscious narrative we call the mind.

@Constance: Neurons just do that because they can? What motivates these neuronal pyrotechniques? Our neurons do not produce our experiences in and of the world, they respond to them, organize and integrate them, facilitate our responses to what happens. The brain facilitates consciousness and mind, which originate in our interactions with our actual surrounding environment. At every stage of the evolution of species, an organism's lived experience in the world expands its awareness of itself and its mileau.

@Soupie: What do you mean by “our experiences” in this context? If by our experiences, you mean our physical interaction with the world, then yes, I agree.

We are physical beings physically interacting with a physical world.

However, the question is, why are we subjects of phenomenal experience. Why does it feel like something to be physical beings physically interacting with the physical world?

So, I would make a distinction between our physical bodies having physical, causal “experiences” with the physical world, and the phenomenal, narrative experience that -- at least for humans -- accompanies our physical being in the world.

We don’t have an answer for why this phenomenal experiential narrative exists. We just don’t. However, when the brain -- and namely clusters of neurons -- is damaged, the stream/waves of phenomenal, feeling, something-it-is-like is effected. Hence, there’s seems to be some special relationship between neurons and consciousness. Just what that relationship is, we don’t know.

-----

@smcder: the combination problem nervous systems and brains develop under biological/chemical/physical constraints and so the combination problem involves that the structure of the brain, so constrained, still coincides with the "structure" of the mind - but this gives up the advantages of panpsychism, of mind being fundamental, so that it's very hard not to have a "psycho-physical nexus" or not to think in terms electrity:wires software:computer ... even though you disclaim this, your model looks an awful lot like that ... (if not, what metaphor would you use to describe the brain/mind relationship? I think you've used excreted or generated?)

@Soupie: Let’s say that Susan has not been born yet. On my approach, neither her brain nor her mind exists yet. (Never mind metaphysical questions about time, yada, yada.)

I think wherever there is matter (whatever that is) there is mental. So elementary particles (whatever they are) “carry” with them a mental property. This is fundamental.

[Now, what I’m not clear on, is whether particles are themselves a result of interaction and/or relationship. That is, if a particle is really the result of a relationship between X and Y, that means “fundamental” properties are also a result of this relationship. So in other words, when I use the term fundamental, I’m really just saying it’s something that just is, but we haven’t a clue why… like, why do matter, energy, and fields exist? We don’t know.]

So all matter has mental. But not all material structures/processes have minds, or at least minds like ours.

As you know, there is no metaphor that can capture the unique relationship of matter and mind. Using a metaphor about matter relating to matter will not capture matter relating to mind.

I do think the matter-information is the best metaphor (and I believe of course that it may be more than a metaphor).

I say that mental is a fundamental property of all matter, but that not all material structures have minds (like ours).

I can say that all material structures can be said to embody information (form), but that not all material structures embody information that constitutes a mind (like ours).

I think our bodies/brains embody intentional information. What is intentional information? It is information about something. What does this mean? It means one physical form is “about” another physical form.

So a beautiful picture of a woman is about a real woman. The picture embodies intentional information of the woman.

All interacting, fundamental particles by way of their interactions with one another can be said to carry information about one another.

Intentional information is everywhere. Experience is everywhere. Mental is everywhere. Panpsychism.

The human brain by way of neurons, embodies intentional information that has somehow become self-aware. So as Susan’s brain develops and grows, so too does the intentional information it embodies. If the brain is damaged, the mind is damaged.

The brain embodies intentional information (form) that is aware that it is about some other physical form. When we experience the sun, our physical body is being physically changed. When know that our experience of the sun is about something.

Our brain is a painting that is aware that it is a painting.

That is, I think consciousness can exist in-itself (the mind is green), but that consciousness can exist for-itself (I am seeing something green). I think what we experience as our conscious narrative is consciousness for-itself.

[However, as we know, one of the amazing things about quasi-physical information, is that it is substrate independent. It can travel from physical substrate to physical substrate. So my thoughts move from my brain to the actions of my fingers on my keyboard. The function of the keyboard causes software to encode my thoughts that I translated to words into binary code. This code travels as light through the interwebs onto Gene’s server. This code is then decoded and manifested as lighted pixels on your screens. That light is received by your retinas. Your retinas transduce this light into electrical pulses that travel on your optic nerves into your brains/neurons. You (read: not your neurons) then read/decode the words, and derive meaning from them.

This is all to say that I would still consider myself a dualist. I think the brain and the mind are distinct. There may be some circumstances wherein the human mind exists apart from the physical brain with which it was once associated.

Last edited:

Soupie

Paranormal Adept

@smcder: I myself can't see how this happens ... how something of a different order altogether (experience) arises from electro-chemical interactions. And I don't think you can see it either, I think you are simply claim it - based on the idea of emergence, but emergence itself isn't something you can see or have any intuitions about - it's just a statement that more complex things come out of interactions according to simple rules.

If you do actually see this, then what imagery, what metaphor, what comparisons, what intuitions fo you have about it and can you make to something that we do know about?

@Soupie: I’m not claiming that phenomenal experience arises from electro-chemical interactions.

I’m saying that phenomenal experience/feeling is fundamental. I’m not saying -- in this present discussion -- that feeling emerges from two neurons firing together. (Although it might.)

I’m saying that feeling is fundamental to all interactions of matter/energy. Fundamental = It just is.

Then what I’m saying is that the actions of neurons (and perhaps other special physical structures) interacting with one another in such a way facilitate the shaping of this fundamental experience/feeling into what we know as our phenomenal, narrative landscape.

So, no, I can’t see how “phenomenal feeling” emerges from matter, hence phenomenal feeling is fundamental.

Yes, I can see how a process of billions of integrated, synchronizing neurons can take this fundamental, phenomenal feeling and shape it into a process of experience we call mind.

If you do actually see this, then what imagery, what metaphor, what comparisons, what intuitions fo you have about it and can you make to something that we do know about?

@Soupie: I’m not claiming that phenomenal experience arises from electro-chemical interactions.

I’m saying that phenomenal experience/feeling is fundamental. I’m not saying -- in this present discussion -- that feeling emerges from two neurons firing together. (Although it might.)

I’m saying that feeling is fundamental to all interactions of matter/energy. Fundamental = It just is.

Then what I’m saying is that the actions of neurons (and perhaps other special physical structures) interacting with one another in such a way facilitate the shaping of this fundamental experience/feeling into what we know as our phenomenal, narrative landscape.

So, no, I can’t see how “phenomenal feeling” emerges from matter, hence phenomenal feeling is fundamental.

Yes, I can see how a process of billions of integrated, synchronizing neurons can take this fundamental, phenomenal feeling and shape it into a process of experience we call mind.

Pharoah

Paranormal Adept

The weight of opinion against HCT and Evans on lexical concepts is considerable and historic. But these opposing views do look remarkably silly. For an intersting appraisal of this area see first introductory pages from:Thanks very much for that reference. I was going to ask you for an approach to contrast with Evans's.

Apropos of that, read the review of the pamphlet on OOO by Graham Harman posted just above.

ps: there's something for all of us there.

Radical concept nativism by Stephen Laurence, Eric Margolis.

@Constance: Except, as Panksepp has pointed out, the seeds of protoconsciousness have germinated before neurons have evolved in the evolution of living organisms, revealed in the 'affectivity' and 'seeking behavior' recognizable in primordial organisms and, indeed, even in the earliest single-celled organism observed and described by Maturana and Varela and termed 'autopoiesis'.

Actually, I thought we determined that Panksepp’s “Affective Neuroscience” was indeed based on neurons?

I don't remember our ever coming to agreement or even mutual understanding among ourselves concerning Panksepp's recognition of affectivity and seeking behavior in primordial organisms lacking neurons [prior to the development of neurons in subsequent evolution of species]. We read some papers by Panksepp in Part 2 of this thread, around the time when Pharoah suggested that we move our discussion to a Google thread he set up for that purpose. It was Pharoah who brought Panksepp's research into our discussions and he communicated with him briefly, sharing a text describing HCT with him, after which their interaction ceased (so far as I know). I continued to read Panksepp and cited and quoted his papers concerning the pre-neuronal affectivity and seeking behavior in the Google thread, but no one else took this material up. If the Google thread is still available, I'll go back and cite those sources again. I've referred again to these recognitions of Panksepp's from time to time in Parts 2 and 3 (and now again in part 4) but to my recollection no responses have ever been expressed here by the rest of you. I think we ought to go back and read those papers by Panksepp because they are highly ramifying for a neuron-based attempt to account for protoconsciousness and consciousness.

From wiki:

“Affective neuroscience is the study of the neural mechanisms of emotion. This interdisciplinary field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood.[1]”

We can't expect wiki to provide more than a general take on Panksepp's research and thinking as a whole.

S

smcder

Guest

@smcder: I myself can't see how this happens ... how something of a different order altogether (experience) arises from electro-chemical interactions. And I don't think you can see it either, I think you are simply claim it - based on the idea of emergence, but emergence itself isn't something you can see or have any intuitions about - it's just a statement that more complex things come out of interactions according to simple rules.

If you do actually see this, then what imagery, what metaphor, what comparisons, what intuitions fo you have about it and can you make to something that we do know about?

@Soupie: I’m not claiming that phenomenal experience arises from electro-chemical interactions.

I’m saying that phenomenal experience/feeling is fundamental. I’m not saying -- in this present discussion -- that feeling emerges from two neurons firing together. (Although it might.)

I’m saying that feeling is fundamental to all interactions of matter/energy. Fundamental = It just is.

Then what I’m saying is that the actions of neurons (and perhaps other special physical structures) interacting with one another in such a way facilitate the shaping of this fundamental experience/feeling into what we know as our phenomenal, narrative landscape.

So, no, I can’t see how “phenomenal feeling” emerges from matter, hence phenomenal feeling is fundamental.

Yes, I can see how a process of billions of integrated, synchronizing neurons can take this fundamental, phenomenal feeling and shape it into a process of experience we call mind.

Yes, I can see how a process of billions of integrated, synchronizing neurons can take this fundamental, phenomenal feeling and shape it into a process of experience we call mind.

And I don't think you can't actually "see" this in any meaningful way ... and you can't understand "how" in any meaningful way ... what you really mean by I can see how is just that you think it could be the case that ... and that's based on a metaphorical sense of fundamental phenomenal feeling be something that can be shaped ... into a "process of experience" (what is a process of experience)?

If not, then you can explain to me how?

To my mind that is the misleading thing about emergence and its metaphors - above you make it sound like some stuff is "shaped" into a process of experience ... yet there is no "stuff" and no "shaping" going on ... and "process of experience" doesn't really mean or tell us anything. Or do you think consciousness, mind, these fundamental things are like (or are) a fluid or malleable substance?

I am trying to nit pick and push you on this - because although it would be easy to say sure, I know what you mean ... I think the real case is like virgins talking about sex.

If you don't root out the underlying metaphors it's too easy to follow through with the idea that mind and consciousness is some kind of "stuff" and right now, I do think such ideas are misleading.

Last edited by a moderator:

S

smcder

Guest

The weight of opinion against HCT and Evans on lexical concepts is considerable and historic. But these opposing views do look remarkably silly. For an intersting appraisal of this area see first introductory pages from:

Radical concept nativism by Stephen Laurence, Eric Margolis.

Have you heard of dyslexie or other fonts for dyslexic readers?

- Status

- Not open for further replies.