Chirimutta points out that "Color points out to the world of objects, and at the same time it draws us inward to examine the perceptual subject."

What's disclosed thereby is the interpenetration of subjectivity and objectivity in the world as we can and do experience it, an interpenetration explicated in phenomenological analysis, not just by philosophers but by we ourselves when, if, we reflect on the nature of our experience.

The world we live in is real, actual, and the consciousness we bear into it discloses this world partially, perspectivally, temporally -- in the changing natural affordances of light enabling us to perceive things in the world moment-by-moment and from various perspectives we achieve by walking around the objects that we encounter.

Objects are real; they are not to be confused in their actual, if temporal, existence with the quantum activity that appears to be the substrate of the physically evolved world in which we live. We come closer to understanding the actual nature of the objects we encounter by multiplying our own perspectives upon them, and more fully by combining our individual perspectives and resulting descriptions with those achieved by others.

An adequate ontological description of the world we live in and disclose, to the extent(s) that we can, is a work in progress that our species (no doubt like other species of life elsewhere in the universe) engage in collectively and pluralistically in order to achieve maximum access to and 'grip' on 'what-is'. All reductive presuppositions [such as, most dominantly, the objectivist presuppositions of modern science] are the enemies of progress in our understanding of the complex nature of reality.

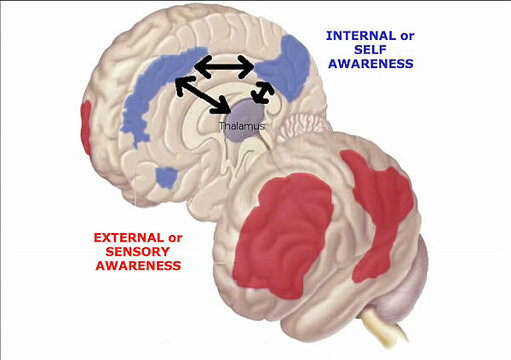

Science has long avoided, indeed ignored, the evidence of the subjectivity of human perception, experience, and mind. Neurophenomenology is the best hope for a correction of that error, now that consciousness has finally become the subject of interdisciplinary research.

What's disclosed thereby is the interpenetration of subjectivity and objectivity in the world as we can and do experience it, an interpenetration explicated in phenomenological analysis, not just by philosophers but by we ourselves when, if, we reflect on the nature of our experience.

The world we live in is real, actual, and the consciousness we bear into it discloses this world partially, perspectivally, temporally -- in the changing natural affordances of light enabling us to perceive things in the world moment-by-moment and from various perspectives we achieve by walking around the objects that we encounter.

Objects are real; they are not to be confused in their actual, if temporal, existence with the quantum activity that appears to be the substrate of the physically evolved world in which we live. We come closer to understanding the actual nature of the objects we encounter by multiplying our own perspectives upon them, and more fully by combining our individual perspectives and resulting descriptions with those achieved by others.

An adequate ontological description of the world we live in and disclose, to the extent(s) that we can, is a work in progress that our species (no doubt like other species of life elsewhere in the universe) engage in collectively and pluralistically in order to achieve maximum access to and 'grip' on 'what-is'. All reductive presuppositions [such as, most dominantly, the objectivist presuppositions of modern science] are the enemies of progress in our understanding of the complex nature of reality.

Science has long avoided, indeed ignored, the evidence of the subjectivity of human perception, experience, and mind. Neurophenomenology is the best hope for a correction of that error, now that consciousness has finally become the subject of interdisciplinary research.

And now that we know how we will certainly engage you if necessary! ;-)

And now that we know how we will certainly engage you if necessary! ;-)