Merleau-Ponty's Human-Animality Intertwining and the Animal Question

Louise Westling, University of Oregon

Abstract: Maurice Merleau-Ponty's late work locates humans within a wild or brute being that sustains a synergy among life forms. His Nature lectures explored the philosophical implications of evolutionary biology and animal studies, and with The Visible and the Invisible describe a horizontal kinship between humans and other animals. This work offers a striking alternative to Heidegger's panicky insistence on an abyss between humans and other animals that Derrida questions but cannot seem to discard. For Merleau-Ponty, literary works probe the invisible realm of wildness that is our only environment, a realm full of language and meaningfully experienced by all animals.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty's late work defines a chiasmic ontology in which human

experience is part of a wild or brute being that sustains all life and provides a synergy among its distinct forms. His

Nature lectures at the Collège de France explored the philosophical implications of modern science, including evolutionary biology and animal studies, and together with the unfinished manuscript of

The Visible and the Invisible gestured toward a horizontal kinship between humans. This work offers a striking alternative to Heidegger's panicky insistence on the abyss between humans and other animals, an abyss that Derrida questions but cannot seem to discard in

The Animal that Therefore I Am.

Matthew Calarco wonders why Derrida would resolutely refuse to abandon the human/animal distinction and "why he would use this language of ruptures and abysses when the largest bodies of empirical knowledge we have concerning human beings and animals strongly contest such language."1 But Derrida explicitly resists any claims of "biological continuism, whose sinister connotations we are well aware of . . . ."2 As a Jew he might have been particularly aware of the cruel history of Social Darwinism, eugenics and animal coding for abjecting human groups during the twentieth century. However, accepting a continuum between our species and

1

Zoographies: The Question of the Animal from Heidegger to Derrida (New York: Coumbia U P, 2008) pp. 145, 147. Further citations will be in parentheses in the text.

2 The Animal That Therefore I Am, ed. Marie-Louise Mallet and trans. David Wills (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), pp 30-31.

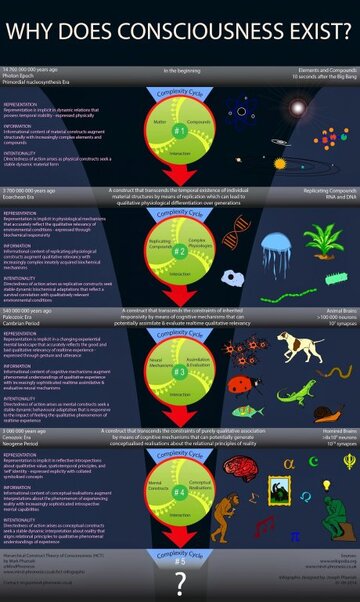

other creatures need not lead to extremes such as Social Darwinism or some of the excesses of sociobiology and Neo-Darwinism which include humans within mechanistic and reductionist descriptions of organic behavior. A continuum would instead imply that many kinds of consciousness and perception evolved over the hundreds of millennia of life's emergence. Human sentience would then be understood as one of many kinds of animal awareness, as the work of Jakob von Uexküll asserts. Neither humans nor other animals could then be dismissed

deterministically as mechanisms; instead they would have to be recognized as active participants shaping the many meanings of the biological community. This is the minority position voiced so strongly in the Renaissance by Montaigne in "The Apology for Raymond Sebond" and by Darwin in The Descent of Man in the nineteenth century.3

Evolutionary biology, recent archeological finds, and empirical animal studies have

erased much of the distance between homo sapiens and our coevolved animal relatives such as the great apes, dolphins, elephants, and even parrots.4 The Humanist tradition of insistence on our separateness from the rest of the animal community seems increasingly absurd, in ways that Merleau-Ponty's proto-ecological philosophy anticipated. Although he acknowledged the

distinctive qualities of human communication and art, he saw them as having developed from gestural meaning that is fully enmeshed in the phenomenal world. The varieties of human

3 Calarco sees Derrida's position as a solution to a false dilemma, a choice between extremes of complete separation between humans and other animals, or reductive homogeneity, Zoographies, p. 149.

4 See for example Lynn Margulis, Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution (New York: Basic Books, 1998); Nicholas Wade, Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors (New York: Penguin, 2006); Stephen Mithin, After the Ice: A Global Human History (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard U P, 2004); Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, "Chapter 1: Bringing Up Kanzi" in Apes, Language, and the Human Mind. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, Stuart G. Shanker, and Talbot J. Taylor (New York: Oxford U P, 1998), pp. 3-74; Frans De Waal, The Ape and the Sushi Master: Cultural Reflections of a Primatologist (New York: Basic Books, 2001); Caitlin O'Connell. The Elephant's Secret Sense: The Hidden Life of the Wild Herds of Africa (Chicago: U Chicago P, 2008); and Irene Pepperberg, Alex and Me (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2008).

speech are our particular ways of "singing the world."5 For him, literary works probe the invisible realm of wildness that is our only environment, a realm that he saw as full of language and meaningfully experienced by all animals. Strangely Merleau-Ponty is rarely mentioned by most participants in the recent spate of critical animal studies stimulated by Derrida's reevaluation of Heidegger's position.6 In these

writings, only Donna Haraway, Matthew Calarco, and Cary Wolfe have seriously challenged Derrida's resistance to the idea of biological continuism. Why might that be, when Merleau-Ponty's work so closely accords with much postmodern theory as well as with the concerns of present environmental and animal studies debates? Already in the 1950s he was moving beyond human exceptionism and seriously exploring the philosophical consequences of biological and ethological research. Taylor Carman and Mark Hansen believe one reason is that Merleau-Ponty's premature death prevented the full development of his philosophical project. They also suggest that his reputation fell victim to the radical spirit of 1968 which led a younger generation including Derrida, Lacan, and Foucault to lump Merleau-Ponty together with Husserl and Sartre and to accuse phenomenology of humanist focus on consciousness, or subjectivism.7

That charge could not have been made if his late writings and lectures had been well

known. Not only did he reject that kind of focus on human consciousness, but his lifelong engagement with science took him well beyond the positions of other phenomenologists.8 His attitude toward scientific thought was not uncritical,

5 Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. Colin Smith (London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 179, 187.

6 See for example, Giorgio Agamben, The Open: Man and Animal (Stanford, Stanford U P, 2004); Kelly Oliver, "Stopping the Anthropological Machine: Agamben with Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty." PhaenEx 2 (Fall/Winter 2007): 1-23; Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008); Timothy Morton, "Ecologocentrism: Unworking Animals." SubStance 117 (2008): 73-96; Calarco, Zoographies, see Note 1 above; and the PMLA special "Animal Studies" series in Vol. 124 (March 2009): 472-575, especially Cary Wolfe's contribution, "Human, All Too Human: 'Animal Studies' and the Humanities," 564-575.

7 Introduction, The Cambridge Companion to Merleau-Ponty. Ed. Taylor Carman and Mark B. N. Hansen (New York: Cambridge U P, 2008) p. 22.

8 Merleau-Ponty's position on human-animal relations in this late work is complicated by its unfinished quality. The posthumously published manuscript of The Visible and the Invisible was relatively polished and carefully worked out as far as it went, but as translator Robert Vallier explains, the Nature lectures are preserved only in an anonymous student's notes and Merleau-Ponty's own scribbled notes for the final course of 1959-1960. See "Translator's Introduction," Nature: Course Notes from the Collège de France, compiled and with notes by Dominique Sélgard and trans. Robert Vallier (Evanston: Northwestern U P, 2003) p. xiv. Even so, the notes show Merleau-Ponty testing out the meaning of specific research in the life sciences and exploring their philosophical consequences.

however, for he believed it to be limited by objectivism and its failure to acknowledge its situatedness within culture. For him, "classical science is a form of perception which loses sight of its origins and believes itself complete;"9 its theories and schematizations are "an abstract and derivative sign-language, as is geography in relation to the countryside in which we have learnt beforehand what a forest, a prairie or a river is."10 But he also saw that scientists provided the most carefully regulated available attention to the natural world. All through his career he closely connected his arguments to relevant scientific research. In particular he relied upon Gestalt psychology and the disciplines of neuroscience during the 1930s and 1940s; and explored physics, animal studies, human physiology, and evolutionary biology in the 1950s. He saw philosophy and science as complementary explorations of the world and thus necessarily engaged in productive dialogue with one another.

The Visible and the Invisible is unequivocal in asserting the essential wildness of Being and the intertwining or chiasmic relationships among all creatures and things in the dynamic unfolding of reality through evolutionary time. Human beings, like all other living things, are immersed in this flesh of the world, within "a spatial and temporal pulp where the individuals are formed by differentiation."11 Within this flesh, species and individual organisms manifest not only formal resemblances but also identical constituting substances, i. e. atoms, molecules, and microorganisms that embody or mirror biological macrocosms. Heidegger would be horrified to think that each human or other animal body was itself a symbiotic community of many tinier bodies. Yet this new understanding would not have troubled Merleau-Ponty, who asked, "Why would not the synergy exist among different organisms, if it is possible within each? Their landscapes interweave, their actions and their passions fit together exactly . . . ."12 When Alphonso Lingis describes the hundreds of bacteria inhabiting our mouths to neutralize plant toxins or those digesting the food in our intestines,13 he is extending this point to recent discoveries about the genetic and cellular make-up of our bodies which came long after Merleau-Ponty's death but which show that the symbiotic intertwinings within each organism do indeed mirror those outside them. But Merleau-Ponty's concepts of écart and dehiscence account for distinctions among living creatures at the same time that there is kinship and continuism. The analogy he uses to explain this situation is that of our two hands both touching and being touched by each other, both parts of the same body but also distinct from each other. As it is with our two hands, so it is also between our conscious awareness of our body and its inaccessible inner thickness, between our movements and what we touch, and between us and other kindred creatures. This is a synergy of "overlapping and fission, identity and difference."14

In the

Nature lectures, Merleau-Ponty acknowledged biological continuism by

considering the meaning of new work in evolutionary biology and discussing the silent emergence of humans and their horizontal relationship to other species that Teilhard de Chardin had defined in

The Phenomenon of Man . . . ."

continue at:

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/49ba/77e030c3eec09b5b44a56de7725f4d1a9049.pdf

Thanks for the link @smcder