Pharoah

Paranormal Adept

Philosophy Now series. Hegel's Phenomenology by Richard NormanLol. I wish I had a suggestion at hand for a better introduction to Hegel's phenomenology, but there must be one. What is the text you're using?

NEW! LOWEST RATES EVER -- SUPPORT THE SHOW AND ENJOY THE VERY BEST PREMIUM PARACAST EXPERIENCE! Welcome to The Paracast+, eight years young! For a low subscription fee, you can download the ad-free version of The Paracast and the exclusive, member-only, After The Paracast bonus podcast, featuring color commentary, exclusive interviews, the continuation of interviews that began on the main episode of The Paracast. We also offer lifetime memberships! Flash! Take advantage of our lowest rates ever! Act now! It's easier than ever to susbcribe! You can sign up right here!

Philosophy Now series. Hegel's Phenomenology by Richard NormanLol. I wish I had a suggestion at hand for a better introduction to Hegel's phenomenology, but there must be one. What is the text you're using?

I am reading the posts...Now when I ran that by @Pharoah (who I hope is, per my instructions, currently ignoring me on the forum (to a mutually higher end ) he said this was almost exactly it ... but I think he too misses the force of Nagels critique only to rewrite it as the problem of the noumenal - and that's why it doesn't make sense to us when he says ive solved the hard problem, long live the hard problem in the form of the noumenal ... because they are the same ding dang thang.

I hope that @Pharoah has not put your posts on 'ignore', Steve, because we need all our points of view present if we are to work on the hard and harder problems of consciousness. In doing so, with Pharoah's further participation here, we will be able to understand what he means by the 'noumenal'. I am now most eager to hear from him about the connection he sees between the noumenal and the plurality of consciousnesses experienced among our species and others.

Question: will 'hard' and 'harder' do as terms by which to distinguish the general significance of consciousness in biological organisms and the more ramifying significance of the plurality of consciousnesses/subjectivities worlding the world we live in on earth and also, most probably, elsewhere in the universe?

Yesterday @Pharoah wrote in a response to me that

I am interested to hear from Pharoah how his theory accounts for the kinds of 'adaptation' that occur in the human mind that emerges in stage 4, which constitute an explosive plurality of unique subjectivities.

Philosophy Now series. Hegel's Phenomenology by Richard Norman

I am reading the posts...

When I refer to "the Hard Problem of consciousness", I am referring to David Chalmers' paper. Namely, "the hard problem is the problem of experience" - phenomenal experience.

If HCT is a reductive explanation of phenomenal experience, then phen exp is not a hard problem. i.e. Chalmers is wrong. Furthermore, I reject the conclusion of Jackson's knowledge argument with my critique of it (an argument that is vigorously defended by Chalmers, though now rejected by Jackson himself).

I do think there is a hard problem but it has nothing to do with phenomenal experience. The hard problem for me is explaining why I am me, rather than anyone else. The first-person perspective is explainable - namely why first-persons exist and why they possess this qualitative conscious perspective. The hard question in my view is, why is my first-person mine and not any other first-person in the universe of time and space? It is a hard question because it is person specific and not a general rule of physics about first persons.

The reason why Chalmers thinks phen exp is the hard problem, is because he attaches the concept of phen exp to the concept of the specifics of his own conscious self, and he does that because he is an anti-physicalist. HCT separates the two issues of one's own conscious and the general characteristics of consciousnesses.

Inevitable in the sense that certain "phenomena" will arise, i.e., complex life. But not in the deterministic sense.

I'm a visual person. Help me out. Imagine that the universe is a cube with marbles in it.

If natural teleology is true, how would the box and marbles behave? If X is true (where X is whatever you and Constance mean when you say "reductive/determined"), how would the box and marbles behave? You will probably decline, and if so, I will give it a go, and then you can question my two visualizations.

I am reading the posts...

When I refer to "the Hard Problem of consciousness", I am referring to David Chalmers' paper. Namely, "the hard problem is the problem of experience" - phenomenal experience.

If HCT is a reductive explanation of phenomenal experience, then phen exp is not a hard problem. i.e. Chalmers is wrong. Furthermore, I reject the conclusion of Jackson's knowledge argument with my critique of it (an argument that is vigorously defended by Chalmers, though now rejected by Jackson himself).

I do think there is a hard problem but it has nothing to do with phenomenal experience. The hard problem for me is explaining why I am me, rather than anyone else. The first-person perspective is explainable - namely why first-persons exist and why they possess this qualitative conscious perspective. The hard question in my view is, why is my first-person mine and not any other first-person in the universe of time and space? It is a hard question because it is person specific and not a general rule of physics about first persons.

The reason why Chalmers thinks phen exp is the hard problem, is because he attaches the concept of phen exp to the concept of the specifics of his own conscious self, and he does that because he is an anti-physicalist. HCT separates the two issues of one's own conscious and the general characteristics of consciousnesses.

@smcder Why did I need to read that article, "The Secrets of Consciousness and the Problem of God"?

I am reading the posts...

When I refer to "the Hard Problem of consciousness", I am referring to David Chalmers' paper. Namely, "the hard problem is the problem of experience" - phenomenal experience.

If HCT is a reductive explanation of phenomenal experience, then phen exp is not a hard problem. i.e. Chalmers is wrong. Furthermore, I reject the conclusion of Jackson's knowledge argument with my critique of it (an argument that is vigorously defended by Chalmers, though now rejected by Jackson himself).

I do think there is a hard problem but it has nothing to do with phenomenal experience. The hard problem for me is explaining why I am me, rather than anyone else. The first-person perspective is explainable - namely why first-persons exist and why they possess this qualitative conscious perspective. The hard question in my view is, why is my first-person mine and not any other first-person in the universe of time and space? It is a hard question because it is person specific and not a general rule of physics about first persons.

The reason why Chalmers thinks phen exp is the hard problem, is because he attaches the concept of phen exp to the concept of the specifics of his own conscious self, and he does that because he is an anti-physicalist. HCT separates the two issues of one's own conscious and the general characteristics of consciousnesses.

@smcder Why did I need to read that article, "The Secrets of Consciousness and the Problem of God"?

Okay, so maybe intentionless inevitability wasn't too far off?With natural teleology I think it means that given a set of pre-conditions that make life possible, then life will move inevitably toward more complexity and toward certain configurations, ie intelligence, self awareness.

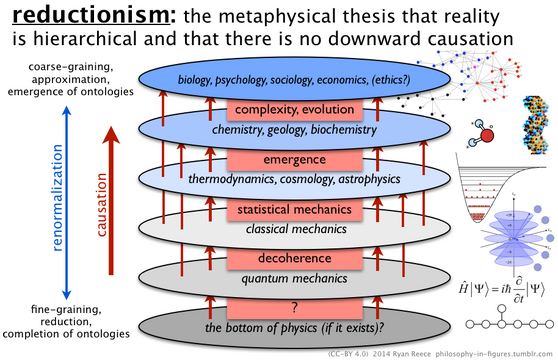

Speaking of Thaddius Roberts, he just retweeted this image:

philosophy in figures : Photo

Where/how does natural teleology relate to metaphysical reductionism?

It's ole Thad! Yeah, no mental causation, not to mention consciousness is not fundamental. I suppose things at the bottom will be "fundamental."

Re plurality of consciousness. Frankly, I don't see why a physicalist would see this as a problem.

It's ole Thad! Yeah, no mental causation, not to mention consciousness is not fundamental. I suppose things at the bottom will be "fundamental."

Okay, so maybe intentionless inevitability wasn't too far off?

I was thinking we could take a little more license with the box and marbles.

As far as I can tell, the only difference between current orthodoxy and natural teleology, is that the "shape of the box" ie the natural laws, lead to, not just life, but complex life (perhaps possessing consciousness?).

Current orthodoxy, if I understand correctly, says our universe is "eerily" tuned for the emergence of life. Natural teleology simply says its tuned for the inevitable emergence of complex life.

What do you think?

Steve wrote: Breaking it out piece by piece:

article: Nagel’s deepest question about consciousness is not provoked by the sheer fact of conscious experience.

Pharoah: I do think there is a hard problem but it has nothing to do with phenomenal experience.

article: It’s the plurality of consciousness that’s strange. No objective scientific account of all the elements in the universe could say why I am me and you are you.

Pharoah: The hard problem for me is explaining why I am me, rather than anyone else. ...

Pharoah: The hard question in my view is, why is my first-person mine and not any other first-person in the universe of time and space? It is a hard question because it is person specific and not a general rule of physics about first persons.

article: No objective scientific account of all the elements in the universe could say why I am me and you are you.

How do @Constance and @Soupie read these comparisons?

I'm not sure what you're looking for. I now see the hard problem on two levels, the first being the standard hard problem of qualitative experience expressed by Chalmers, and the second focused on the 'harder problem'* of the plurality and distinctiveness of individual consciousnesses. I think this plurality and distinctiveness of consciousness also exists among the higher animals. We humans are simply the most radical extension of consciousness on this planet, to our knowledge. I think it's clear that subjectivity and consciousness have evolved in the history of living organisms. Whether we can locate a fundamental 'physical origin' of consciousness somewhere deep in nature is an interesting question, but not the focus of my own interest in what consciousness is and what it enables. What it enables wherever it exists is awareness of the world, realization of parts and aspects of the world, cognizing of the world as a whole and our relationship in and toward it, and as MP wrote a "singing of the world." It is the world brought to numberless partial and various forms of light and appreciation that life produces in it.

* re 'the harder problem': I'm not sure yet that this is actually a separate problem or a problem at another level.

Yes, Ive read that article several times. I think the author and Pharaoh are describing the same problem.I was curious as to what you made of the texts I laid out above - between @Pharoah's ideas of the noumenal and Nagel's formulation as reported in the article?

I don't know if Tononi is a physicalist, but the next paragraph of that same article may be helpful (note that the references to God are as a type of consciousness, a thought experiment but I don't get the impression that the author's argument turns on the existence of such a mind)

Tononi, like a lot of other neurologically influenced scientists, from William James to Oliver Sacks, is fascinated by neural deficits and accidents that fracture consciousness into independent and plural consciousness. Most notoriously, people whose corpus callosum has been cut (often to control epilepsy), so that the two sides of their brains can no longer communicate with each other, thenceforth have two consciousnesses, each as separate from the other as “the breach from one mind to another,” which William James notably described as “perhaps the greatest breach in nature.” In such cases, it seems that either one consciousness can be turned into two, or that it’s a mistake to talk of a single consciousness. I think Tononi must be right to interpret this disturbing phenomenon by showing that consciousness doesn’t correspond to some Platonic soul. But that only makes consciousness, if possible, still more mysterious, still harder to imagine understanding, since once again we’re confronted not with a single phenomenon — consciousness itself — but the irreducible plurality of different consciousnesses.

Tononi offers a weak answer to this question: qualia belong to me if they’re sort of me-shaped. That seems right but woefully insufficient. It still doesn’t give us a way of understanding not that objects are different from each other but rather that subjects are. Nothing explains why I’m me, just as nothing could explain to the monster — not even his creator Frankenstein— why he is who he is, just as nothing could explain to God why God is God.

Unlike many of his neuroscientist colleagues, Tononi doesn’t really think he’s solved the problem of consciousness. He knows that his suggestions are jury-rigged. As his book progresses, he confronts the feebleness of science in the face of the phenomena it discovers. One reads this book with a kind of burgeoning terror at the complex vulnerabilities of the brain, the only place in the universe that the mind assuredly exists. Tononi seems just as grimly clear-sighted about this as any philosopher or poet. Science wants to know all, to be omniscient. But the study of the brain and its relation to consciousness seems to prove that even if scientists could play God (“the Brain is just the weight of God,” Dickinson concludes), even if they did achieve divine omniscience, they could never know how any other consciousnesses could exist, nor whether they did exist, nor how there could be a plurality of them. Gibson’s Dixie Flatline and Tononi’s Galileo don’t, in fact, have sentience. They’re fictional characters. How could any science, any omniscience, know that we were more real than they?

. . . Is this not the same idea of the hard problem? And is it not Chalmers and Nagels and Pharoahs? And if so, then there is only one problem the hard problem and it's not been solved?