"Naive Realism and the Hard Problem of Consciousness; Or the Story of Captain Homunculus."

Excellent work!

Very clever, @Soupie.

NEW! LOWEST RATES EVER -- SUPPORT THE SHOW AND ENJOY THE VERY BEST PREMIUM PARACAST EXPERIENCE! Welcome to The Paracast+, eight years young! For a low subscription fee, you can download the ad-free version of The Paracast and the exclusive, member-only, After The Paracast bonus podcast, featuring color commentary, exclusive interviews, the continuation of interviews that began on the main episode of The Paracast. We also offer lifetime memberships! Flash! Take advantage of our lowest rates ever! Act now! It's easier than ever to susbcribe! You can sign up right here!

"Naive Realism and the Hard Problem of Consciousness; Or the Story of Captain Homunculus."

Excellent work!

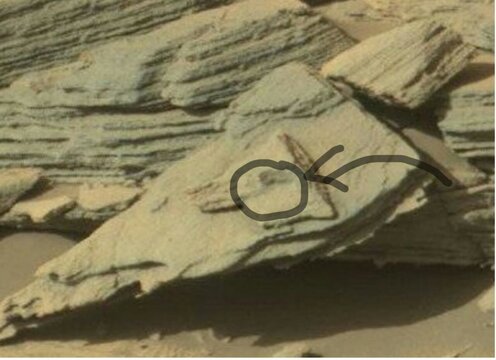

This additional crop (below) from JPL's higher resolution version of the image might help. The critter (if critter it is) is poised near the center of the roughly triangular rock face filling most of the cropped image. It appears to be clinging to the rough edge of an additional rock sitting atop the larger rock face that is shaped something like a wolf's head in profile. It looks fleshy and spotted (like several large snakes visible in an earlier Mars panorama I've seen -- one intact and another one nearby cut up in pieces). If this critter is an arthropod of some sort as we know them on earth, it seems both like and unlike those evolved here in several respects. It has a smooth fleshy body in its upper (thorax?) area and a segmented body toward the back. Several black leg-like appendages appear along its visible left side.

Photo by constance523

Because of the flatness and dullness of most raw JPL panoramas of Mars rover images released to the public [largely the result of the orange filter applied over most of them, and made worse in images obtained in lower light conditions depending on the weather and time of day], it is necessary to increase the light and contrast in the photos and adjust the tone and hue of colors registered in the photos in order to see objects with greater definition and depth. The reason why I first saw this 'critter' as such is that while I was enhancing light, contrast, and color information available in the raw image of Curiosity MSL 1301, Right Mastcam, I suddenly saw this 'critter' emerge on a rock face simultaneous with a subconscious startle reaction, just as I would experience in the first moment before directly perceiving a similar critter in my kitchen. I first realized the activity of my own subconscious mind when we had dogs who sometimes dragged their leashes into the living room. On repeated occasions, coming home from work and looking through the mail I'd brought in from the post box, my subconscious perception of shapes in the field of my peripheral vision would sense one of these leashes as a possible snake and I would experience that startle reaction, drawing my focal vision instantly to a place on the floor where I saw in fact a leather dog leash.

The same thing happened when I first perceived the appearance of this possible critter in the JPL SOL 1301 image. Are the signs presented in the image sufficient to claim that I/we are looking at a Martian arthropod similar enough to the arthropods studied on earth? I'm looking for an entomologist willing to look at this image and speculate about its possible nature.

Here is a link to the full resolution version of the JPL SOL 1301 image with no light or color enhancements made:

Raw Images - Mars Science Laboratory

{scroll down and click on the link from there to the full resolution image}

The issues of consciousness and the nature of being were only to provide examples upon which a response could be given rather than an expression of my own viewpoint. In this way I had hoped to get some idea how the minds that responded to it were looking at the issues. You responded in a way I didn't expect, which was rather than providing your way of looking at the issues, you posed questions about the question itself. That has led us here.You seem to be sidestepping the critical issues concerning the ambiguity, the imprecision, of terms and concepts I raised in response to your last post.

We can start by identifying weather or not the core idea is internally coherent. To do that we only need to be sure that the terms used are considered in the context they were meant to be considered by the author of the idea. I find that in philosophy, it's not wise to assume that words that appear to mean something relatively familiar, actually represent what we might think they do. For example the word "intentionality". However provided that we interpret the terms correctly, it's not always necessary to invoke all the minutiae every philosopher in history has had to contribute in order to evaluate whether or not the core concepts have specific strengths and weaknesses.Re your underscored statement above -- "I tend to seek better explanations through an analysis of competing ideas, which is an entirely different approach," -- my question is on what basis we can 'analyze competing ideas' without analyzing the empirical, experiential, basis out of which they are developed.

Which is probably why I find that phenomenology compares well with psychology.Unlike materialist/physicalist/objectivist science of our time, phenomenology analyzes experiential {lived} reality from first-person, second-person, and third-person perspectives, not merely to "facilitate change in those who have more fixed beliefs," but to open our species' minds to the perspectival and thus partial nature of the variously afforded capacities of our -- and other species' -- perceptions of what-is and the ways in which these various perspectives overlap to disclose a commonly shared 'world' -- a local world -- in which we are both embedded and enactive in our ongoing senses of and activity within it.

Yes, ontological questions usually do concern the nature of being. We don't usually concern ourselves with the ontology of comedy, at least not my brand of comedy. What was that you called it again? "70s humor" or something to that effect ... lol. But you might find this paper refreshing:In general we humans have taken this local world to constitute the 'reality' within which we, individually and collectively, have existed and developed our various ways of life (cultures) within it. But our own experiences of being-in-this-world have long led our species to pose ontological questions concerning the nature of being -- and of Being -- beyond the horizons of that which is visible, sensible, and knowable by us at this point in our own evolution.

Do we need to be rationally justified? I don't think so. It seems that we can contemplate whatever we want without any rational justification whatsoever. Indeed, I think that in order to more fully appreciate some things we need to set aside our rational processing and focus on the experience of the moment.Are we rationally justified in contemplating our existential being-in-situation [temporally and spatially]

OK. If we take "beginning with increased understanding of that which we experience." as a "beginning" ( a starting point ), that makes experience the foundation for further inquiry, and because much of what we experience is perceptual, perceptual experience might be seen as the structural elements on top of that foundation, and in the context of inquiry, those elements have been dubbed "empirical evidence". From there the application of our cognitive abilities has illuminated the wealth of knowledge we have today, which makes these many realizations, flashes of insight, whatever you want to call them, experiences that are elevated above that of the raw sensory perception that led us to them.as we experience it as an expression of the nature of being on planetary worlds beyond our own, and further as an expression of the nature of the Being of All-that-Is? What else can we rely on in our thinking? Hardened concepts [ideas] of what-is as developed at earlier stages in our species' existence, dismissed one by one over our history? Or the dominant computational meme characterizing our own Western culture? We need both philosophy and science, and other disciplines of human thinking and expression, to make progress in our understanding of 'what-is' in the local world we exist in, beginning with increased understanding of that which we experience.

Text for the day, a metaphor posed by Merleau-Ponty: "The fish is in the water and the water is in the fish."

This additional crop (below) from JPL's higher resolution version of the image might help. The critter (if critter it is) is poised near the center of the roughly triangular rock face filling most of the cropped image. It appears to be clinging to the rough edge of an additional rock sitting atop the larger rock face that is shaped something like a wolf's head in profile. It looks fleshy and spotted (like several large snakes visible in an earlier Mars panorama I've seen -- one intact and another one nearby cut up in pieces). If this critter is an arthropod of some sort as we know them on earth, it seems both like and unlike those evolved here in several respects. It has a smooth fleshy body in its upper (thorax?) area and a segmented body toward the back. Several black leg-like appendages appear along its visible left side.

Photo by constance523

Because of the flatness and dullness of most raw JPL panoramas of Mars rover images released to the public [largely the result of the orange filter applied over most of them, and made worse in images obtained in lower light conditions depending on the weather and time of day], it is necessary to increase the light and contrast in the photos and adjust the tone and hue of colors registered in the photos in order to see objects with greater definition and depth. The reason why I first saw this 'critter' as such is that while I was enhancing light, contrast, and color information available in the raw image of Curiosity MSL 1301, Right Mastcam, I suddenly saw this 'critter' emerge on a rock face simultaneous with a subconscious startle reaction, just as I would experience in the first moment before directly perceiving a similar critter in my kitchen. I first realized the activity of my own subconscious mind when we had dogs who sometimes dragged their leashes into the living room. On repeated occasions, coming home from work and looking through the mail I'd brought in from the post box, my subconscious perception of shapes in the field of my peripheral vision would sense one of these leashes as a possible snake and I would experience that startle reaction, drawing my focal vision instantly to a place on the floor where I saw in fact a leather dog leash.

The same thing happened when I first perceived the appearance of this possible critter in the JPL SOL 1301 image. Are the signs presented in the image sufficient to claim that I/we are looking at a Martian arthropod similar enough to the arthropods studied on earth? I'm looking for an entomologist willing to look at this image and speculate about its possible nature.

Here is a link to the full resolution version of the JPL SOL 1301 image with no light or color enhancements made:

Raw Images - Mars Science Laboratory

{scroll down and click on the link from there to the full resolution image}

Thank you so much, Steve, for finding and posting this link to a wide range of Stevens's own readings of his poetry

I read the list of recordings and discovered near the end of it a lecture by one of the most insightful literary critics responding to Stevens's poetry, A. Walton Litz, who has produced two excellent books on this poetry. This lecture provides a guide to understanding Stevens's poetry based on Litz's own lengthy and comprehensive study of it and resulting insights into it. You have always been interested in the Stevens poems I have posted here at various places in the two years of development of this thread, so you might want to listen to this lecture. Here is the link to it:

{Just click on the arrow to start Litz's lecture.}

We can indeed read the whole of Todes's book online at this link:

Todes - Body and world - Unknown - 2001.pdf

This is a pdf of the entire text by Todes with introductions by both Dreyfus and Piotr Hoffman.

It's a Christmas present from Google.

ETA: Comments are enabled in the DocHub mode of the pdf.

Wonderful! I enjoyed this ... I had never heard of Rachel Lindsay.

I'll try to find and post some of Lindsay's poems later.

I'll try to find and post some of Lindsay's poems later.Literature and philosophy are full of fishy quotes ... in Professor P. Pedantus' opus magnum "Fishy, fishy ... you're all wet! A Compilation of Fishinutiae in Literature and Philosophy" (1989) we find one of the earliest fish tales in the English language in a draft of Shakespeare's Hamlet when the Bard writes:

"Something is fishy in the state of Denmark."

... before later changing it to a more generally rotten reference.

Another early Piscean reference is the old adage that "you can lead a fish to water, but you can't make him sink" - which easily predates the Equestrian version - the proof of this is in the original formulation "You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him sink." which was common for about 500 years before gradually taking its more familiar potable formulation by way of numerous intermediary forms: "think, stink, shrink, clink ... " etc etc

The great philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich ("Freddy Boy" or "Stinky" to his friends) Hegel was also known to make the odd fish reference in his public lectures when he would suddenly pause and eructate:

"Es gibt einen Fisch in meiner Dialektik!"

To this day, no one is really sure what he meant, but a small cottage industry has grown up around possible explanations and is the fodder of intense late night sessions at the annual New Jersey Continental Philosophy conference held every year in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Of course reference works like Professor Pedantus' are now obsolete with the advent of Google. Leading social critic Aleksander Kidztuday believes the word Google naturally decomposes in the mind to the command phrase "Go Ogle" and thus excites the prurient interests of its users.We cannot lightly dismiss this work as neuroscientists have recently found that approximately 10% of people have Google-receptors in their brain (and a con-comitant 10% decrease in independent and creative thought) It's not clear if this is an environmental adaptation, a defensive response to overexposure or a recent mutation - ... other minority theorists support the idea that it is an indication that we are living in a simulation.

This theory is colloquially known as "the fishbowl hypothesis"

Vachel Lindsay, an American bard of the twenties and thirties who preferred to speak or chant his poems on the streets and traded poems for food and shelter during the Depression. Somewhere I have two of the first published volumes of his poetry given to me by a fellow undergraduate English major, Ted Krug, at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. Now happily remembering that gentle relationship again.I'll try to find and post some of Lindsay's poems later.

What a contrast to Stevens' poetry and life.

Did you keep up with Mr. Krug at all after graduation?

Naive Realism and the Hard Problem of Consciousness; Or the Story of Captain Homunculus

One day Captain Homunculus was navigating his submarine about the ocean's depths. As always, he used his radar to navigate. All the marine master knew of the world came to him via his radar system.

His radar system was top notch. It sent out a steady array of pings which the system used to present a picture of the world to Captain Homunculus on his radar screen. For instance if there were a whale in front of the vessel, a long, beautiful, skinny red blob would appear on the screen. If there were an iceberg he would see the blobby red shape of an inverted cone. If there were a mountain thrusting up from the ocean floor, he would see a blobby, red, majestic pyramid.

One curious day, our nautical hero saw something on the radar screen that surprised him. What had at first appeared to be a tiny circle soon grew into a large circle. The captain thought that a torpedo of some kind was traveling toward him. He quickly responded by turning the sub in an effort to avoid the watery weapon. However, when the submarine was perpendicular to the approaching object, its shape changed. It changed from a large circle shape into a large cigar shape. After some additional maneuvering and experimenting, our homunculian hero realized that what he was seeing (on his radar screen) was himself.

He quickly surmised that there must be a "mirror" in the ocean that was causing his radar system to see itself. Captain Homunculus had never seen himself before. He moved the submarine up and down and side-to-side, and in that way was able to get a look at the entirety of the sub. And not to his surprise his submarine seemed to share nearly the exact same size and shape as other submarines he had encountered. On the front of the cylindrical, underwater boat, he could even see a little, square, maroon blob. That must be the radar system. Fascinating. He had always wondered what it looked like, and now he knew.

But in this insightful moment of self discovery, a thought occurred to him. When he reflected on the inside of the sub, it was rich with detail; but when he looked outside the submarine at his reflection in the mirror, he saw only the (admittedly handsome,) crimson red cigar. Inside, rich; outside, only red. Moreover, he thought, his fellow submarines must also have equally rich innards.

This puzzled him for several minutes. His radar system was top notch. It had been developed by the best engineers over dozens of years. And he had sailed around the ocean from North to South and from East to West. He had seen every sight in the known world. His radar system had never failed him.

And then the answer struck him, and he felt rather silly. He simply needed to position his radar so he could see the inside of a submarine. Not the outside.

In the months following this thought-provoking experience, he pondered how he might get a glimpse of the inside of a submarine. And he spoke with other submarines, and they confirmed that they did indeed have innards that were rich like his, but also confirmed that the world seemed indeed to consist of an altogether different, blobby, red substance. They supported his endeavor to look at the inside of a submarine.

And then one day, it happened. Our nautical navigator and several friends were traveling in the crusty northern seas. They were marveling at the beautiful variety of marine life swimming amongst the dangerous iceberg fields through which they were moving. A myriad of gorgeous maroon objects of various shapes and sizes moving in a plethora of directions at varying speeds. It was a magical moment. Until tragedy struck.

One of the Captain's friends, absorbed in the beauty of the moment no doubt, drifted too close to one of the icebergs and its razor sharp, crimson edges. The buoyant red mountain sliced the poor submarine clean in half.

Homunculus could only watch in horror.

He and the other submarines were able to retrieve both halves of the sub. It was a long, solemn trip back home to where they were able to give their beloved friend a proper burial.

...

At the time, the friends were too grief stricken to speak of it, but all of them had seen it just the same. And it had only added to the horror and confusion of the moment. When at last they had had the opportunity to see the inside of a submarine, indeed their poor friend, the inside was every bit as red and blobby as any other object they had ever seen in their lives. Granted, there was a certain complexity to the inside of their friend, but the richness of their innards was nowhere to be seen amongst the blobby crimson complexity.

Or perhaps absent altogether, as some began to wonder. Others, especially an eccentric Australian vessel, suggested that explaining how one could get the rich variety of their innards from the shapely, crimson processes that appeared on their radar screens was a uniquely hard problem.

However, some scoffed at this proclamation as being mere rhetoric. These individuals insisted that they simply needed to look harder, develop better, more precise radar systems and then surely they would be able to see on their radar screens the innards of others in exactly the same way that they saw everything else.

The humble Homunculus was surprised—and bewildered—to learn that some poor fools had even caught the notion that everything—including whales, icebergs, and radar systems themselves—were made of the same stuff as his, and their, innards. But how icebergs, whales, and radar systems could be made of non-blobby red stuff--stuff that didn't appear on radar screens--was so hard to fathom as to make the question laughably absurd.

These pathetic pirates even claimed that while submarine radar was top notch, the beautiful, detailed, crimson images on the radar screen were perceptions of the world, and not to be confused with the world in-itself.

An easy rebuttal, our hero thought, was that most submarines, most of the time, were in complete agreement regarding what they saw in the world. How could this be possible if what their radar was showing them was not the world as it really was?

No, his rich, inner world was real, not an illusion. And he was equally certain that the beautiful, crimson outer world was real too, and not an illusion.

Maybe the world did consist of two substances. Or maybe he did simply need better radar. He certainly agreed with the Aussie fellow that explaining how his rich, inner world was produced by the blobby, crimson processes he observed in the world was certainly a hard problem.

I keep the question about "contentless awareness" vs. all consciousness is consciousness of something in mind ... not sure Husserl would have known about the states of mind claimed to be "contentless awareness" and I came across something on "pure consciousness" as a limit to phenomenological analysis - will try to find the Husserl quote ...

2.) what would a state of confusion be about? there is consciousness there ... but what is it exactly that one is aware of when in a confused state? What is the phenomenology of confusion?

I'm not clear about the proposed nature of "contentless awareness" or the texts that develop this idea. Can you clarify this idea for me and cite the authors who propose and/or examine it, adding perhaps your own experiences of what you might think of as 'contentless awareness' reached in your own meditative practice?

I think it is the phenomenological recognition of the reality of 'prereflective awareness' that we still need to explore in this thread. I've referred to prereflective awareness numerous times in this thread but evidently not clarified yet what it is. Dreyfus, in his introduction to Todes's Body and World, takes up this subject at the outset, but does not imo clarify its phenomenological meaning sufficiently. SEP has an article entitled "Phenomenological Approaches to Self-Consciousness" by Shaun Gallagher and Dan Zahavi that does a far better job of clarifying what 'prereflective awareness' is and the reasons why phenomenologists recognize it as a form of consciousness ==> 'prereflective consciousness' of the environing 'world' that is the ground out of which reflective consciousness and mind develop. I'll quote below extracts from the first two sections of this article and link to the whole article at the end of my post. After reading even the first section of this article it should be clear why prereflective consciousness itself already implicates 'self-consciousness' -- a state of lived being without which conscious beings could not begin to reflect on and think about the nature of their own consciousnesses.

"Phenomenological Approaches to Self-Consciousness

First published Sat Feb 19, 2005; substantive revision Wed Dec 24, 2014

On the phenomenological view, a minimal form of self-consciousness is a constant structural feature of conscious experience. Experience happens for the experiencing subject in an immediate way and as part of this immediacy, it is implicitly marked as my experience. For phenomenologists, this immediate and first-personal givenness of experiential phenomena is accounted for in terms of a pre-reflective self-consciousness. In the most basic sense of the term, self-consciousness is not something that comes about the moment one attentively inspects or reflectively introspects one's experiences, or recognizes one's specular image in the mirror, or refers to oneself with the use of the first-person pronoun, or constructs a self-narrative. Rather, these different kinds of self-consciousness are to be distinguished from the pre-reflective self-consciousness which is present whenever I am living through or undergoing an experience, i.e., whenever I am consciously perceiving the world, whenever I am thinking an occurrent thought, whenever I am feeling sad or happy, thirsty or in pain, and so forth.

- 1. Pre-reflective self-consciousness

- 2. One-level accounts of self-consciousness

- 3. Temporality and the limits of reflective self-consciousness

- 4. Bodily self-awareness

- 5. Social forms of self-consciousness

- 6. Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Pre-reflective self-consciousness

One can get a bearing on the notion of pre-reflective self-consciousness by contrasting it with reflective self-consciousness. If you ask me to give you a description of the pain I feel in my right foot, or of what I was just thinking about, I would reflect on it and thereby take up a certain perspective that was one order removed from the pain or the thought. Thus, reflective self-consciousness is at least a second-order cognition. It may be the basis for a report on one's experience, although not all reports involve a significant amount of reflection.

In contrast, pre-reflective self-consciousness is pre-reflective in the sense that (1) it is an awareness we have before we do any reflecting on our experience; (2) it is an implicit and first-order awareness rather than an explicit or higher-order form of self-consciousness. Indeed, an explicit reflective self-consciousness is possible only because there is a pre-reflective self-awareness that is an on-going and more primary self-consciousness. Although phenomenologists do not always agree on important questions about method, focus, or even whether there is an ego or self, they are in close to unanimous agreement about the idea that the experiential dimension always involves such an implicit pre-reflective self-awareness.[1] In line with Edmund Husserl (1959, 189, 412), who maintains that consciousness always involves a self-appearance (Für-sich-selbst-erscheinens), and in agreement with Michel Henry (1963, 1965), who notes that experience is always self-manifesting, and with Maurice Merleau-Ponty who states that consciousness is always given to itself and that the word ‘consciousness’ has no meaning independently of this self-givenness (Merleau-Ponty 1945, 488), Jean-Paul Sartre writes that pre-reflective self-consciousness is not simply a quality added to the experience, an accessory; rather, it constitutes the very mode of being of the experience:

"This self-consciousness we ought to consider not as a new consciousness, but as the only mode of existence which is possible for a consciousness of something (Sartre 1943, 20 [1956, liv]).

The notion of pre-reflective self-awareness is related to the idea that experiences have a subjective ‘feel’ to them, a certain (phenomenal) quality of ‘what it is like’ or what it ‘feels’ like to have them. As it is usually expressed outside of phenomenological texts, to undergo a conscious experience necessarily means that there is something it is like for the subject to have that experience (Nagel 1974; Searle 1992). This is obviously true of bodily sensations like pain. But it is also the case for perceptual experiences, experiences of desiring, feeling, and thinking. There is something it is like to taste chocolate, and this is different from what it is like to remember what it is like to taste chocolate, or to smell vanilla, to run, to stand still, to feel envious, nervous, depressed or happy, or to entertain an abstract belief. Yet, at the same time, as I live through these differences, there is something experiential that is, in some sense, the same, namely, their distinct first-personal character. All the experiences are characterized by a quality of mineness or for-me-ness, the fact that it is I who am having these experiences. All the experiences are given (at least tacitly) as my experiences, as experiences I am undergoing or living through. All of this suggests that first-person experience presents me with an immediate and non-observational access to myself, and that (phenomenal) consciousness consequently entails a (minimal) form of self-consciousness. In short, unless a mental process is pre-reflectively self-conscious there will be nothing it is like to undergo the process, and it therefore cannot be a phenomenally conscious process (Zahavi 1999, 2005, 2014). An implication of this is obviously that the self-consciousness in question can be ascribed to all creatures that are phenomenally conscious, including various non-human animals.

The mineness in question is not a quality like being scarlet, sour or soft. It doesn't refer to a specific experiential content, to a specific what; nor does it refer to the diachronic or synchronic sum of such content, or to some other relation that might obtain between the contents in question. Rather, it refers to the distinct givenness or the how it feels of experience. It refers to the first-personal presence or character of experience. It refers to the fact that the experiences I am living through are given differently (but not necessarily better) to me than to anybody else. It could consequently be claimed that anybody who denies the for-me-ness of experience simply fails to recognize an essential constitutive aspect of experience. Such a denial would be tantamount to a denial of the first-person perspective. It would entail the view that my own mind is either not given to me at all — I would be mind- or self-blind — or is presented to me in exactly the same way as the minds of others.

There are also lines of argumentation in contemporary analytical philosophy of mind that are close to and consistent with the phenomenological conception of pre-reflective self-awareness. Alvin Goldman provides an example:

"[Consider] the case of thinking about x or attending to x. In the process of thinking about x there is already an implicit awareness that one is thinking about x. There is no need for reflection here, for taking a step back from thinking about x in order to examine it…When we are thinking about x, the mind is focused on x, not on our thinking of x. Nevertheless, the process of thinking about x carries with it a non-reflective self-awareness (Goldman 1970, 96)."

A similar view has been defended by Owen Flanagan, who not only argues that consciousness involves self-consciousness in the weak sense that there is something it is like for the subject to have the experience, but also speaks of the low-level self-consciousness involved in experiencing my experiences as mine (Flanagan 1992, 194). As Flanagan quite correctly points out, this primary type of self-consciousness should not be confused with the much stronger notion of self-consciousness that is in play when we are thinking about our own narrative self. The latter form of reflective self-consciousness presupposes both conceptual knowledge and narrative competence. It requires maturation and socialization, and the ability to access and issue reports about the states, traits, dispositions that make one the person one is. Bermúdez (1998), to mention one further philosopher in the analytic tradition, argues that there are a variety of nonconceptual forms of self-consciousness that are “logically and ontogenetically more primitive than the higher forms of self-consciousness that are usually the focus of philosophical debate” (1998, 274; also see Poellner 2003). This growing consensus across philosophical studies supports the phenomenological view of pre-reflective self-consciousness.

That pre-reflective self-awareness is implicit, then, means that I am not confronted with a thematic or explicit awareness of the experience as belonging to myself. Rather we are dealing with a non-observational self-acquaintance. Here is how Heidegger and Sartre put the point:

"Dasein [human existence] as existing, is there for itself, even when the ego does not expressly direct itself to itself in the manner of its own peculiar turning around and turning back, which in phenomenology is called inner perception as contrasted with outer. The self is there for the Dasein itself without reflection and without inner perception, before all reflection. Reflection, in the sense of a turning back, is only a mode of self-apprehension, but not the mode of primary self-disclosure (Heidegger 1989, 226 [1982, 159]).

"In other words, every positional consciousness of an object is at the same time a non-positional consciousness of itself. If I count the cigarettes which are in that case, I have the impression of disclosing an objective property of this collection of cigarettes: they are a dozen. This property appears to my consciousness as a property existing in the world. It is very possible that I have no positional consciousness of counting them. Then I do not know myself as counting. Yet at the moment when these cigarettes are revealed to me as a dozen, I have a non-thetic consciousness of my adding activity. If anyone questioned me, indeed, if anyone should ask, “What are you doing there?” I should reply at once, “I am counting.” (Sartre 1943, 19–20 [1956, liii])."

It is clarifying to compare the phenomenological notion of pre-reflective self-consciousness with the one defended by Brentano. According to Brentano as I listen to a melody I am aware that I am listening to the melody. He acknowledges that I do not have two different mental states: my consciousness of the melody is one and the same as my awareness of perceiving it; they constitute one single psychical phenomenon. On this point, and in opposition to higher-order representation theories, Brentano and the phenomenologists are in general agreement. But for Brentano, by means of this unified mental state, I have an awareness of two objects: the melody and my perceptual experience.

"In the same mental phenomenon in which the sound is present to our minds we simultaneously apprehend the mental phenomenon itself. What is more, we apprehend it in accordance with its dual nature insofar as it has the sound as content within it, and insofar as it has itself as content at the same time. We can say that the sound is the primary object of the act of hearing, and that the act of hearing itself is the secondary object (Brentano 1874, 179–180 [1973, 127–128])."

Husserl disagrees on just this point, as do Sartre and Heidegger: my awareness of my experience is not an awareness of it as an object.[2] My awareness is non-objectifying in the sense that I do not occupy the position or perspective of a spectator or in(tro)spector who attends to this experience in a thematic way. That a psychological state is experienced, “and is in this sense conscious, does not and cannot mean that this is the object of an act of consciousness, in the sense that a perception, a presentation or a judgment is directed upon it” (Husserl 1984a, 165 [2001, I, 273]). In pre-reflective self-awareness, experience is given, not as an object, but precisely as subjective experience. For phenomenologists, intentional experience is lived through (erlebt), but does not appear in an objectified manner. Experience is conscious of itself without being the intentional object of consciousness (Husserl 1984b, 399; Sartre 1936, 28–29). That we are aware of our lived experiences even if we do not direct our attention towards them is not to deny that we can direct our attention towards our experiences, and thereby take them as objects of reflection (Husserl 1984b, 424).

To have a self-experience does not entail the apprehension of a special self-object; it does not entail the existence of a special experience of a self alongside other experiences but different from them. To be aware of oneself is not to capture a pure self that exists separately from the stream of experience, rather it is to be conscious of one's experience in its implicit first-person mode of givenness. When Hume, in a famous passage in A Treatise of Human Nature, declares that he cannot find a self when he searches his experiences, but finds only particular perceptions or feelings (Hume 1739), it could be argued that he overlooks something in his analysis, namely the specific givenness of his own experiences. Indeed, he was looking only among his own experiences, and seemingly recognized them as his own, and could do so only on the basis of that immediate self-awareness that he seemed to miss. As C.O. Evans puts it: “[F]rom the fact that the self is not an object of experience it does not follow that it is non-experiential” (Evans 1970, 145). Accordingly, we should not think of the self, in this most basic sense, as a substance, or as some kind of ineffable transcendental precondition, or as a social construct that gets generated through time; rather it is an integral part of conscious life, with an immediate experiential character.

One advantage of the phenomenological view is that it is capable of accounting for some degree of diachronic unity, without actually having to posit the self as a separate entity over and above the stream of consciousness (see the discussion of time-consciousness in section 3 below). Although we live through a number of different experiences, the experiencing itself remains a constant in regard to whose experience it is. This is not accounted for by a substantial self or a mental theater. There is no pure or empty field of consciousness upon which the concrete experiences subsequently make their entry. The field of experiencing is nothing apart from the specific experiences. Yet we are naturally inclined to distinguish the strict singularity of an experience from the continuous stream of changing experiences. What remains constant and consistent across these changes is the sense of ownership constituted by pre-reflective self-awareness. Only a being with this sense of ownership or minenesscould go on to form concepts about herself, consider her own aims, ideals, and aspirations as her own, construct stories about herself, and plan and execute actions for which she will take responsibility.

The concept of pre-reflective self-awareness is related to a variety of philosophical issues, including epistemic asymmetry, immunity to error through misidentification, self-reference, and personal identity. We will examine these issues each in turn.

It seems clear that the objects of my visual perception are intersubjectively accessible in the sense that they can in principle be the objects of another's perception. A subject's perceptual experience itself, however, is given in a unique way to the subject herself. Although two people, A and B, can perceive a numerically identical object, they each have their own distinct perceptual experience of it; just as they cannot share each other's pain, they cannot literally share these perceptual experiences. Their experiences are epistemically asymmetrical in this regard. B might realize that A is in pain; he might sympathize with A, he might even have the same kind of pain (same qualitative aspects, same intensity, same proprioceptive location), but he cannot literally feel A's pain the same way A does. The subject's epistemic access to her own experience, whether it is a pain or a perceptual experience, is primarily a matter of pre-reflective self-awareness. If secondarily, in an act of introspective reflection I begin to examine my perceptual experience, I will recognize it as my perceptual experience only because I have been pre-reflectively aware of it, as I have been living through it. Thus, phenomenology maintains, the access that reflective self-consciousness has to first-order phenomenal experience is routed through pre-reflective consciousness, for if we were not pre-reflectively aware of our experience, our reflection on it would never be motivated. When I do reflect, I reflect on something with which I am already experientially familiar.

When I experience an occurrent pain, perception, or thought, the experience in question is given immediately and noninferentially. I do not have to judge or appeal to some criteria in order to identify it as my experience. There are no free-floating experiences; even the experience of freely-floating belongs to someone. As William James (1890) put it, all experience is “personal.” Even in pathological cases, as in depersonalization or schizophrenic symptoms of delusions of control or thought insertion, a feeling or experience that the subject claims not to be his is nonetheless experienced by him as being part of his stream of consciousness. The complaint of thought insertion, for example, necessarily acknowledges that the inserted thoughts are thoughts that belong to the subject's experience, even as the agency for such thoughts are attributed to others. This first-person character entails an implicit experiential self-reference. If I feel hungry or see my friend, I cannot be mistaken about who the subject of that experience is, even if I can be mistaken about it being hunger (perhaps it's really thirst), or about it being my friend (perhaps it's his twin), or even about whether I am actually seeing him (I may be hallucinating). As Wittgenstein (1958), Shoemaker (1968), and others have pointed out, it is nonsensical to ask whether I am sure that I am the one who feels hungry. This is the phenomenon known as “immunity to error through misidentification relative to the first-person pronoun.” To this idea of immunity to error through misidentification, the phenomenologist adds that whether a certain experience is experienced as mine, or not, does not depend upon something apart from the experience, but depends precisely upon the pre-reflective givenness that belongs to the structure of the experience (Husserl 1959, 175; Husserl 1973a, 28, 56, 307, 443; see Zahavi 1999, 6ff.).

Some philosophers who are inclined to take self-consciousness to be intrinsically linked to the issue of self-reference would argue that the latter depends on a first-person concept. One attains self-consciousness only when one can conceive of oneself as oneself, and has the linguistic ability to use the first-person pronoun to refer to oneself (Baker 2000, 68; cf. Lowe 2000, 264). On this view, self-consciousness is something that emerges in the course of a developmental process, and depends on the acquisition of concepts and language. Accordingly, some philosophers deny that young children are capable of self-consciousness (Carruthers 1996; Dennett 1976; Wilkes 1988; also see Flavell 1993). Evidence from developmental psychology and ecological psychology, however, suggests that there is a primitive, proprioceptive form of self-consciousness already in place from birth.[3] This primitive self-awareness precedes the mastery of language and the ability to form conceptually informed judgments, and it may serve as a basis for more advanced types of self-consciousness (see, e.g., Butterworth 1995, 1999; Gibson 1986; Meltzoff 1990a, 1990b; Neisser 1988; and Stern 1985). The phenomenological view is consistent with these findings.

2. One-level accounts of self-consciousness

It is customary to distinguish between two uses of the term ‘conscious’, a transitive and an intransitive use. On the one hand, we can speak of our being conscious of something, be it x, y, or z. On the other we can speak of our being conscious simpliciter (rather than non-conscious). For the past two or three decades, a widespread way to account for intransitive consciousness in cognitive science and analytical philosophy of mind has been by means of some kind of higher-order theory. The distinction between conscious and non-conscious mental states has been taken to rest upon the presence or absence of a relevant meta-mental state (cf. Armstrong 1968; Lycan 1987,1996; Carruthers 1996, 2000; Rosenthal 1997). Thus, intransitive consciousness has been taken to be a question of the mind directing its intentional aim at its own states and operations. As Carruthers puts it, the subjective feel of experience presupposes a capacity for higher-order awareness, and as he then continues, “such self-awareness is a conceptually necessary condition for an organism to be a subject of phenomenal feelings, or for there to be anything that its experiences are like” (Carruthers 1996, 152). But for Carruthers, the self-awareness in question is a type of reflection. In his view, a creature must be capable of reflecting upon, thinking about, and hence conceptualizing its own mental states if those mental states are to be states of which the creature is aware (Carruthers 1996, 155, 157).

One might share the view that there is a close link between consciousness and self-consciousness and still disagree about the nature of the link. And although the phenomenological view might superficially resemble the view of the higher-order theories, we are ultimately confronted with two radically divergent accounts. The phenomenologists explicitly deny that the self-consciousness that is present the moment I consciously experience something is to be understood in terms of some kind of higher-order monitoring. It does not involve an additional mental state, but is rather to be understood as an intrinsic feature of the primary experience. That is, in contrast to higher-order accounts of consciousness that claim that consciousness is an extrinsic or relational property of those mental states that have it, a property bestowed upon them from without by some further state, the phenomenologists would typically argue that the feature in virtue of which a mental state is conscious is an intrinsic property of those mental states that have it. Moreover, the phenomenologists also reject the attempt to construe intransitive consciousness in terms of transitive consciousness, that is, they reject the view that a conscious state is a state we are conscious of as object. To put it differently, not only do they reject the view that a mental state becomes conscious by being taken as an object by a higher-order state, they also reject the view (generally associated with Brentano) according to which a mental state becomes conscious by taking itself as an object (cf. Zahavi 2004, 2006).

What arguments support the phenomenological claims, however? The traditional phenomenological approach is to appeal to a correct phenomenological description and maintain that this is the best argument to be found. But if one were to look for an additional, more theoretical, argument, what would one find? One line of reasoning found in virtually all of the phenomenologists is the view that the attempt to let (intransitive) consciousness be a result of a higher-order monitoring will generate an infinite regress. On the face of it, this is a rather old idea. Typically, the regress argument has been understood in the following manner. . . . ."

Phenomenological Approaches to Self-Consciousness (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

That's a good question. It arises prominently in investigations of 'perception' that are limited to visual perception of isolated things {often two-dimensional drawings} in which ambiguity is intentionally embedded, such as the Necker Cube. At a deeper level, these experiments reveal that perception is a struggle for comprehension of the shape, structure, and nature of perceived things. In actual lived experience in and of the 'world' in which a living being is embedded {its immediate, local, environing 'world'} things are encountered within 'situations' -- gestalts -- that are sensed before they become visually and otherwise perceived in the evolution of species.

For Dreyfus, I gather, the ambiguity encountered in lived experiences in the three/four-dimensional world {as distinguished from drawings of ambiguous 'things' presented in lab settings} is resolved by the body itself in its direct interactions with and 'grasps' on things. But the body is not closed up within itself; it senses the qualities that impinge upon it within its environing situation, even in the autopoietic state of being exhibited in primordial single-celled organisms as first demonstrated by Maturana and Varela. It is from this sense of 'being-in-a-world'/being-in-a-situation, that evolving species of life develop pre-reflective consciousness in their encounters with things in their 'worlds' and are motivated to achieve a 'grasp' on the things presented in their environment. Such development clearly involves more than a simply visual encounter. It involves multiple senses of the environment, primarily the sense of touch but also additional bodily senses to the extent to which these have evolved in various species that demonstrate both primarily 'affectivity' and then 'seeking behavior' = enabled action.

ETA: It's important to add that in our own experience as human beings we continue to experience our being and the being of the 'world' we live in pre-reflectivity as well as reflectively.