There is a cluster of terms or concepts that may be at work here: substrate, emergence, illusion and identity that it might be helpful if you could clarify their use in terms of the relationship between consciousness (feeling) and matter in your view?

Substrate: a substance or layer that underlies something, or on which some process occurs, ... (Google)

When I refer to consciousness (feeling) as a substrate, I mean it in the sense above, as a layer that underlies the processes of mind and mind-independent processes that we perceive.

Emergence is not a term that is central to my argument, except to say that consciousness-as-substrate must have properties that allow complex processes to emerge within it.

Often the concept of emergence is invoked to explain how consciousness (feeling) could be a property of physical processes. I'm not making that argument.

Illusion, like emergence, is not a term that is central to my argument. What is central to my argument is the role perspective plays in the challenge of understanding how consciousness relates to matter (which I will refer to as the Mind Body Problem [MBP]).

Perspective: a particular attitude toward or way of regarding something; a point of view. (Google)

All perception involves such perspective. When an organism perceives a stimulus, the relationship is X & X1, where X is the stimulus and X1 is the corresponding state of the organism.

There will always be a dissociation between the stimulus and the corresponding state of the organism. They are not identical.

Rather than refer to this relationship as an illusion, we can refer to is as a matter of perspective.

For example, given stimulus X, two different perceiving organisms will assume two different corresponding states, say, X1 and X2.

Thus, each organism will have a unique perspective on any given stimulus. Even a brief review of the literature outlining the physiological state changes associated with perception will provide one with a sense of their immense complexity.

Identity. This one is very tricky because it is a conceptually loaded term. So, I will try clarify here what I mean when I argue that the organism and the mind are "identical."

Imagine that you--a perceiving organism--perceive three objects (stimuli). Let's refer to these three objects as X, Y, and Z. As outlined above, the process of perception involves you--the organism--undergoing state changes as you perceive each of these three objects. Your state changes will correspond with each of these objects, allowing you to perceive them.

However, since we know that there remains a dissociation between each of the corresponding state changes and the objects themselves, we know that your perceptions will be perspectival.

X & X1

Y & Y1

Z & Z1

Let's imagine that X is actually a banana. What we need to understand is that our perception 'banana" is not identical to the corresponding stimulus in front of us in mind-independent reality. There remains the dissociation noted above. And again, as noted, different organisms will have different perspectives on stimulus X.

Let's imagine that Y is actually a flower. Our perception of Y as a 'flower' will differ from a butterfly's perception of Y. There really is stimulus Y out there in mind-independent reality, but there will remain a dissociation between our's and the butterfly's perceptions of stimulus Y.

Now, what if I say that when a human perceives stimulus Z they see a human. We know there is a dissociation between stimulus Z and our perception 'human.' Stimulus Z and the perception 'human' are not identical.

A 'human' is merely our human perspective on stimulus Z. What is stimulus Z? Stimulus Z is the mind.

What I am suggesting is that the Mind Body Problem is a problem of perspective, not ontology.

The mind and body seem to be two distinct "things" only because when we perceive the mind, we see a body.

The body is the mind viewed from the 3rd-person perspective.

The other critic you've had

@smcder is how structures could form within such a consciousness-as-substrate.

It's a question, the critique lies in the lack of an answer ... ;-) It seems to me exactly the same problem (meaning it is just as hard) as the hard problem - how do you get matter from mind? For you, is getting matter from mind easier than getting mind from matter?

Yes, getting matter from consciousness-as-substrate is easier than getting consciousness (feeling) from matter.

How do you get matter from mind?

The answer is that we already do. All 3rd person knowledge comes directly through 1st-person experience (and intersubjective experience).

Said differently: How the mind (consciousness) relates to the body (matter) is an open question, but it is a fact to say that matter is only ever known within (a) the mind.

In other words, we already know that consciousness can contain matter.

Another response is that while consciousness-as-substrate just is feeling, that does not mean that consciousness-as-substrate doesn't have other properties or that other properties cannot or do not emerge from consciousness-as-substrate.

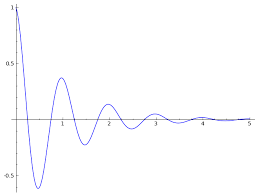

Again, the MBP is an open question. However, via introspection, we know that consciousness (aka the stream of consciousness) is diverse, dynamic, structured, patterned, and differentiated.

So it is self-evident that consciousness (and therefore my theoretical consciousness-as-substrate) is not homogeneous.

Therefore, consciousness (no matter its relation to the body) must have properties which allow it to be heterogenous.

My answer is that this consciousness-as-substrate does have properties that allow it to self-interact.

The question was "how?"

I can't answer that question. But as outlined above, it seems that consciousness (feeling) does indeed have properties that allow it to differentiate.

To answer this question "how," researches will need to continue using the scientific method coupled with phenomenology, while continuing to tease apart (as far as we are able) mind-dependent properties and mind-independent properties.

You might object that as soon as I assert that this consciousness-as-substrate has properties which allow it to evolve and differentiate that I am materializing it.

Maybe you are "substance"-izing it.

Due to the differentiated nature of the mind, it's logical to deduce that consciousness has properties which allow such differentiation.

A physicalist will want to identify physical mechanisms to explain this quality of the mind.

My response would be to say that the perceived physical mechanisms correlated with the stream of consciousness or merely perceptual representiations of more fundamental mechanisms/processes taking place within the consciousness-as-substrate.

The fact that you can always say that, makes it intellectually unsatisfying for some.

I agree. I will continue to think of ways of empirically testing this hypothesis. Obviously, that's going to be problematic considering we can't even empirically prove that anyone is conscious.

Your retort that this is a just-so story until empirical evidence is presented is valid. But one response is that we don't have any reason for accepting the alternative view: that feeling is a property that emerges from physical processes. In fact, given it a HP, we have reason to doubt this view.

I agree! So why chose one view over another if both seem to face equally difficult problems? You don't have to take a view, you could say that no view is currently adequate.

I agree that no view is currently adequate. However, the above view seems to me to have the most going for it at the moment.